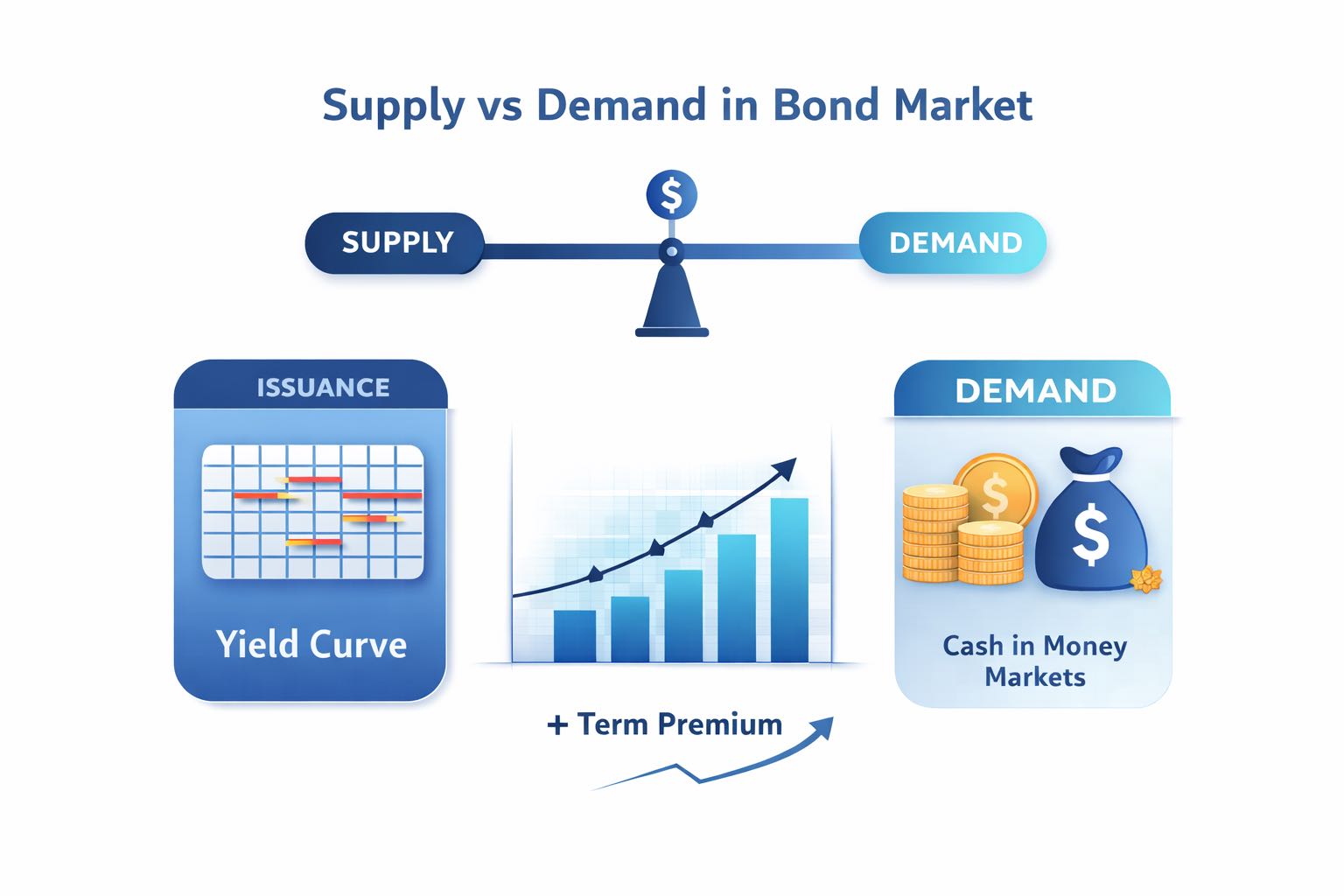

Bond markets are entering 2026 with a familiar tension: stable credit fundamentals on one side, heavy supply on the other. When issuance runs hot, the key variable is not whether borrowers can pay, but what yield the market demands to take down duration in size.

The early-year setup is already visible in the data. Treasury borrowing needs remain substantial into the first quarter, while investment-grade corporates opened January with an unusually dense issuance week. In this kind of tape, pricing often responds first to clearing conditions, auction outcomes, and new-issue concessions, not to a single macro print.

2026 Bond Market Takeaways: Credit vs Supply

Treasury supply sets the risk-free hurdle: When net borrowing stays large, yields can remain sticky even if growth moderates.

Corporate issuance competes for the same marginal buyer: Large primary calendars can widen spreads through concession alone.

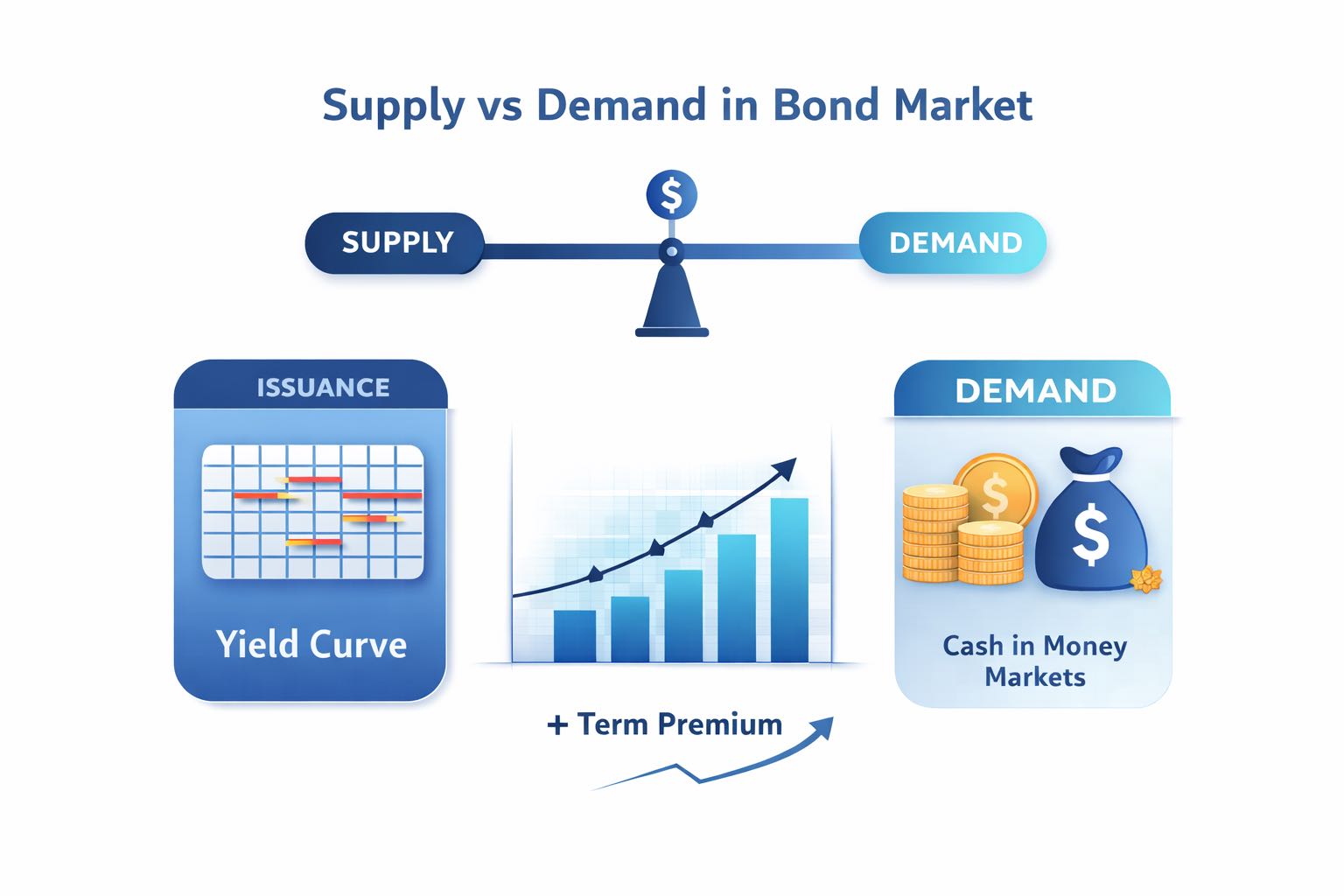

Cash is plentiful, but duration demand is optional: Large money market balances tend to anchor the front end unless investors are paid to extend maturity.

The term premium is doing real work again: A positive term premium keeps the long end sensitive to supply and uncertainty.

The first stress signal is market plumbing: Watch auction tails, bid-to-cover, swap spreads, repo conditions, and the size of new-issue concessions.

Treasury Issuance In 2026: The Rate Floor The Market Must Clear

The simplest way to understand “supply pressure” is to start with Treasury’s own funding estimates. Borrowing needs remain heavy across the turn of the year, which matters because Treasuries are the benchmark that every other borrower prices from.

Supply also matters mechanically. A larger Treasury calendar forces investors to allocate the balance sheet to duration. That can lift yields even in a calm macro backdrop, because the market needs a clearing level that attracts incremental demand.

Treasury buybacks help liquidity, not the deficit

Treasury buybacks are best viewed as a market-functioning tool. Liquidity support buybacks create a regular outlet for off-the-run paper, improving tradability. Cash management buybacks smooth cash balance volatility and bill issuance patterns. Neither is designed to eliminate net borrowing needs, so buybacks do not remove the underlying supply challenge.

Corporate Credit Supply: Stable Fundamentals, Crowded Calendars

The supply story is not only sovereign. U.S. corporate issuance ended 2025 at an elevated level, and 2026 has started with a burst that matters for spreads.

When primary markets get crowded, spreads can widen even if default risk is low. That is not a contradiction. It is how the market rationalizes the balance sheet. A bigger calendar raises the “price of access” through new-issue concession, and secondary spreads often cheapen to compete with fresh supply.

What typically breaks first in a supply-driven selloff

New issues require larger concessions to clear.

Secondary liquidity thins, especially in longer maturities

Spread dispersion rises inside the BBB and lower-quality cohorts.

Issuers with weaker sponsorship lose timing flexibility.

The Marginal Buyer In 2026: Yield-Sensitive And Front-End Heavy

A supply-heavy year tests the buyer base. Two forces define the current setup.

1) The Fed’s balance sheet stance is less of a headwind for Treasuries

The Fed has ended Treasury balance sheet runoff, rolled over maturing Treasuries, and shifted mortgage reinvestments toward Treasury bills. It also began technical bill purchases to support reserve management. That reduces the odds of a steady, mechanical drain in Treasury demand, but it also concentrates support in the front end rather than guaranteeing strong demand for long-dated coupons.

2) Cash has grown, but it does not automatically extend duration

Money market assets are large. That cash pool is a powerful bid for bills and short maturities, but it migrates into longer duration only when the curve offers enough compensation for uncertainty and when investors expect price stability in long bonds.

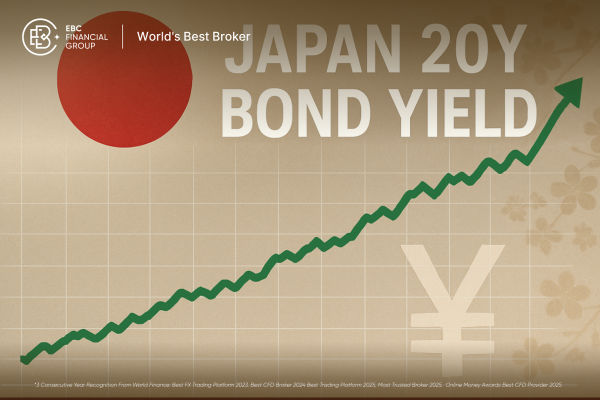

Why Long Yields Can Stay Firm In 2026, Even If Cuts Arrive

The long end is not only a policy-rate story. It is an expectations-plus-term-premium story. When the term premium is positive, long yields can remain elevated even if the market expects some easing over time.

A practical way to frame 2026 is this: if supply stays heavy and inflation uncertainty stays non-trivial, the term premium can do more of the tightening than the policy rate. That keeps duration expensive, and forces credit to clear at higher all-in yields.

Key 2026 Numbers To Track

| Indicator |

Latest Reference Point |

Why It Matters |

| Treasury borrowing needs (near-term) |

Large quarterly net borrowing estimates |

Persistent supply anchors the risk-free curve |

| Money market fund assets |

Near record levels |

Cash is available, but duration demand is conditional |

| Fed balance sheet size |

Still large |

Signals the liquidity regime and front-end support |

| 2-year vs 10-year yields |

Modest positive slope |

Affects carry, hedging costs, and spread demand |

| 10-year term premium |

Positive |

Keeps long yields sensitive to supply |

How To Tell When Supply Is Driving The Market

If supply is the main driver, price action clusters around issuance events rather than macro events. The most reliable real-time signals are:

Auction tails and bid-to-cover: weaker demand forces yields to clear higher.

New-issue concessions: wider concessions signal buyer fatigue.

Swap spreads and repo conditions: balance-sheet scarcity shows up here first.

Spread dispersion: widening gaps between high-quality and marginal borrowers.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. What does “credit vs supply” mean in bond markets?

It describes periods when bond pricing is driven more by issuance volume and buyer capacity than by changes in issuer fundamentals. In those windows, yields and spreads can rise simply because the market needs more compensation to absorb duration and inventory.

2. Can spreads widen even if default risk is stable?

Yes. Spreads include technical and liquidity components. Heavy issuance increases the new-issue concession needed to clear deals, and secondary bonds often cheapen to compete. That repricing can happen without any meaningful change in earnings or balance sheets.

3. Why don’t money market balances automatically support long bonds?

Money market funds primarily buy bills and very short-term paper. Cash moves out the curve when investors expect rate volatility to fall and when term compensation looks attractive. If the term premium rises because of supply uncertainty, that shift can take longer.

4. How does the Fed’s balance sheet stance affect supply pressure in 2026?

Ending Treasury runoff reduces a structural headwind to Treasury demand, but it does not erase net issuance. The Fed’s recent emphasis on bills and reserve management also means the support is more front-end focused than long-end focused.

5. What should investors watch to gauge stress in real time?

Auction metrics, new-issue concessions, repo conditions, swap spreads, and spread dispersion across credit tiers. When these worsen together, the market is usually reacting to clearing pressure rather than to a sudden fundamental break.

Conclusion

The defining bond-market risk in 2026 is not an immediate deterioration in credit quality. It is a clear problem. Treasury funding needs remain large, corporate issuance has started the year at a fast clip, and a positive term premium is keeping long yields sensitive to supply.

In that environment, spreads can widen, and yields can rise simply because the market demands more compensation to hold duration in size.

Disclaimer: This material is for general information purposes only and is not intended as (and should not be considered to be) financial, investment, or other advice on which reliance should be placed. No opinion given in the material constitutes a recommendation by EBC or the author that any particular investment, security, transaction, or investment strategy is suitable for any specific person.