Equity indices move when markets are forced to reprice assumptions that no longer hold. In recent months, those adjustments have been driven less by headlines and more by shifts in yields, changes in earnings expectations, and the level of risk investors are already carrying. What often appears as day-to-day noise is usually the market recalibrating growth prospects, capital costs, and positioning.

Understanding what moves indices most requires focusing on structure rather than stories. Yields reset valuation limits. Earnings expectations determine direction. Positioning and volatility control the speed and intensity of moves, while risk sentiment responds to those mechanics rather than leading them.

Which force dominates depends on where markets sit in the economic and monetary cycle, and that balance has been shifting materially.

What Drives Stock Index Movements

The dominant forces behind index performance can be grouped into five categories, each exerting influence through distinct transmission channels:

Interest rates and bond yields determine equity valuation ceilings and sector leadership.

Earnings growth and guidance anchor the long-term index’s direction.

Positioning and flows amplify or mute fundamental signals.

Risk sentiment governs capital allocation across asset classes.

Volatility regimes dictate market speed, depth, and fragility.

When these forces align, index trends become persistent. When they diverge, markets turn choppy, range-bound, or abruptly unstable.

1. Interest Rates and Yields: The Valuation Anchor

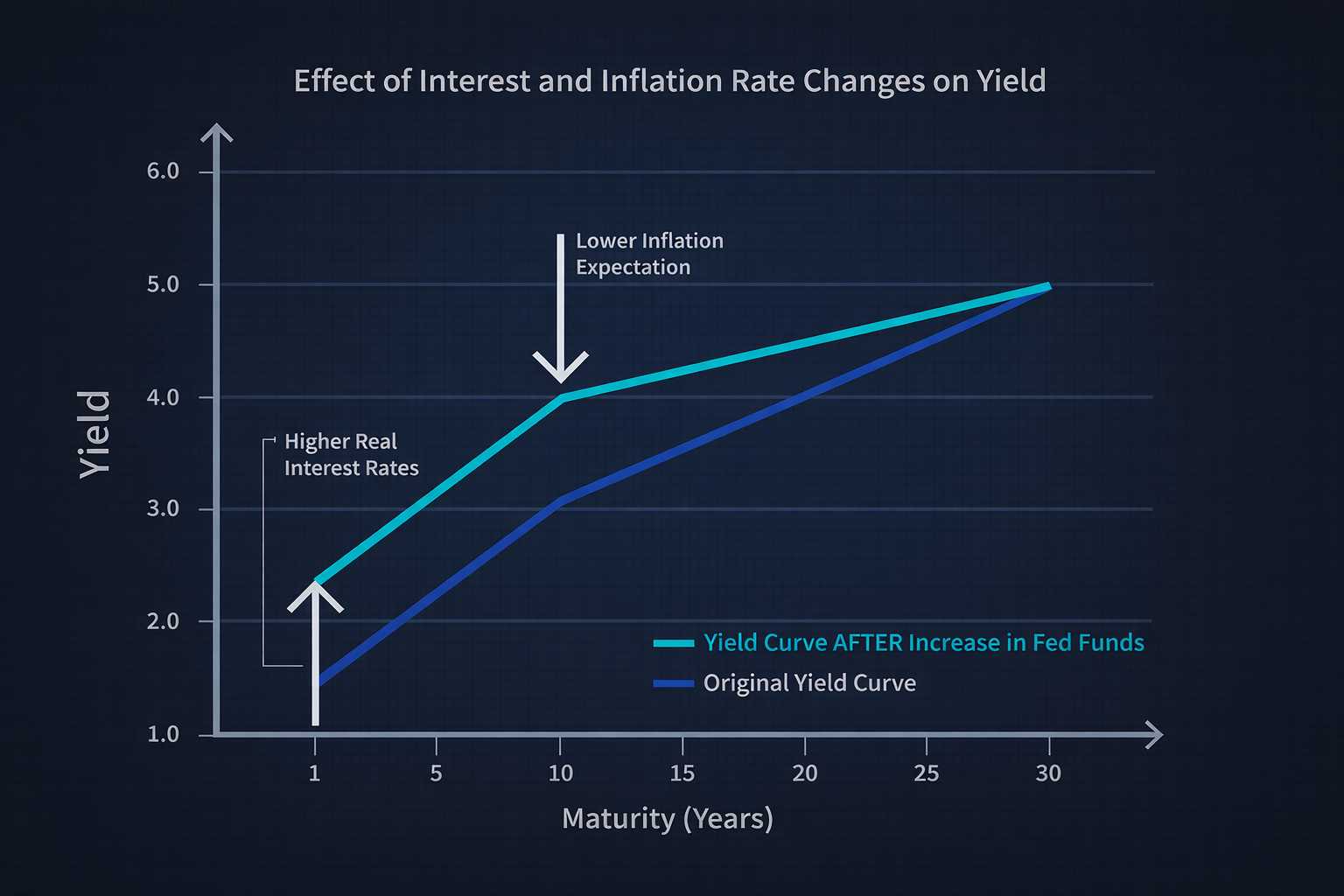

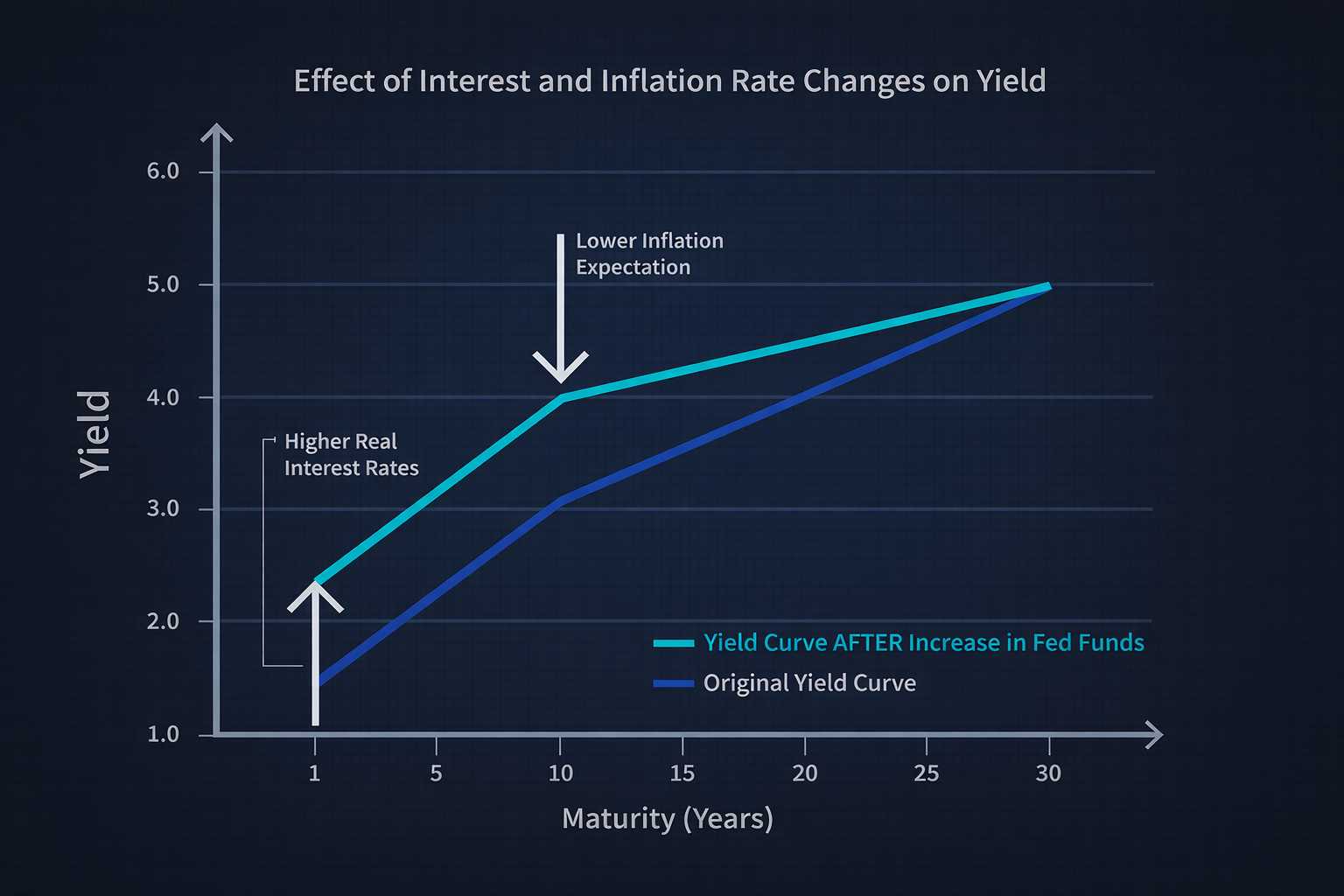

Interest rates sit at the top of the index hierarchy. Equity prices are discounted future cash flows, and the discount rate is directly linked to sovereign yields. Rising yields tighten financial conditions, compress valuation multiples, and favor defensive or value-oriented sectors. Falling yields do the opposite, extending valuation tolerance and supporting duration-heavy equities.

The impact is nonlinear. A gradual rise in yields driven by stronger growth can coexist with rising indices. Abrupt yield spikes, especially when driven by inflation risk or fiscal stress, tend to destabilize equities. Markets react less to the absolute level of yields and more to the speed and source of yield changes.

Central bank expectations play a decisive role here. Shifts in policy pricing around institutions such as the Federal Reserve reshape yield curves and equity risk premiums simultaneously. When policy uncertainty rises, indices struggle to maintain trend consistency even if earnings remain stable.

2. Earnings Season: The Fundamental Gravity

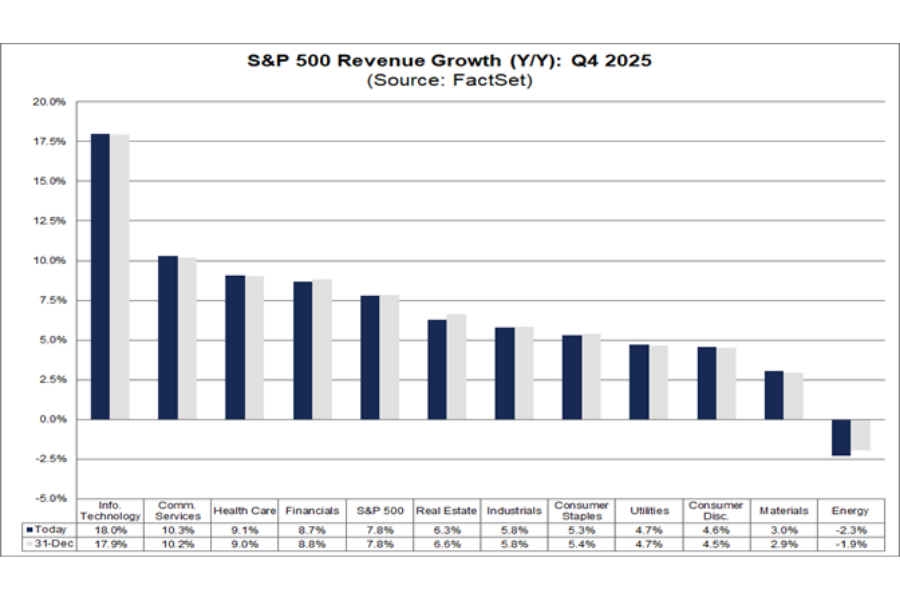

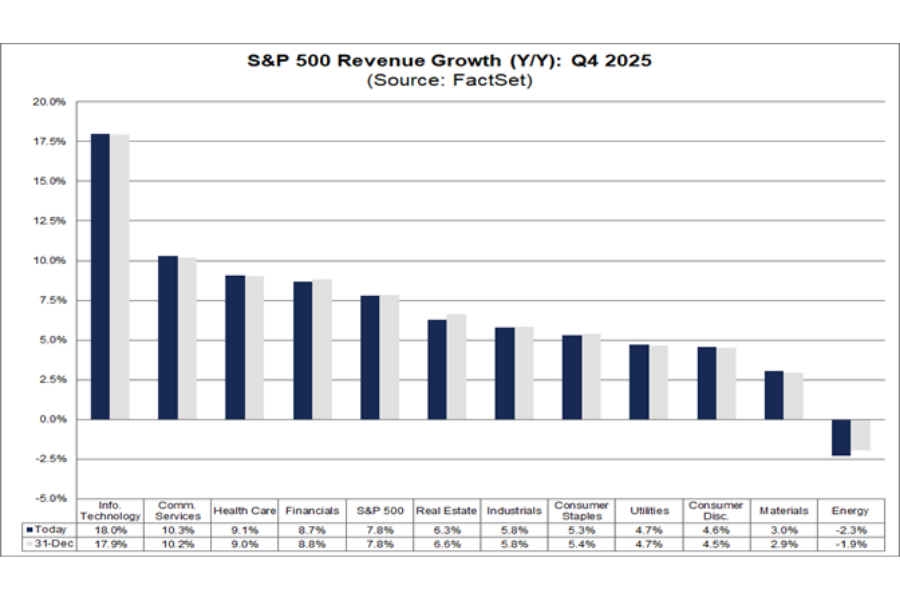

Earnings ultimately justify index levels. Over multi-quarter horizons, sustained index advances require expanding aggregate profits. Revenue growth, margin stability, and forward guidance matter more than headline beats or misses.

What moves indices during earnings season is not isolated results but revision trends. Broad upward revisions to earnings estimates support multiple expansion. Downward revisions, even from elevated levels, impose a ceiling on index performance.

Key margin pressure signals investors monitor include:

Accelerating wage and input cost inflation

Rising net interest expense from tighter financial conditions

Early signs of pricing resistance or demand elasticity

Earnings season also reshapes leadership within indices rather than moving all constituents uniformly. Index performance reflects the weighted outcome of internal rotations driven by earnings visibility and momentum.

3. Positioning and Flows: The Market’s Hidden Lever

Positioning explains why markets can move without new information. When investors are already heavily invested, good news produces limited upside, while negative surprises trigger sharp selloffs. When positioning is light, even modestly supportive data can push markets higher.

Flows matter as well. Shifts in global capital driven by currencies, interest rate gaps, or geopolitical risk can move domestic indices independently of local fundamentals, often for longer than investors expect.

4. Risk Sentiment: The Allocation Engine

Risk sentiment determines whether capital seeks growth or safety. It is expressed through correlations. In risk-on environments, equities, credit, and commodities often rise together. In risk-off phases, correlations converge toward one, and diversification breaks down.

Sentiment is influenced by macro stability, policy credibility, and geopolitical calm. It is fragile when inflation uncertainty is high or when financial conditions tighten unevenly. Indices tend to underperform in sentiment-driven markets because price discovery becomes reactive rather than analytical.

More importantly, sentiment shifts faster than fundamentals. Indices often sell off ahead of economic downturns and recover well before data improves. Reading sentiment requires tracking volatility, credit spreads, and currency behavior alongside the equity prices.

5. Volatility: The Market’s Speed Regulator

Volatility does not dictate direction, but it controls magnitude. A low volatility environment allows leverage, carry strategies, and steady index appreciation. High volatility compresses holding periods, widens bid-ask spreads, and raises the cost of risk.

Volatility spikes often emerge when rates, earnings expectations, and positioning collide. A surprise in any one of these areas can cascade through derivatives markets, forcing mechanical rebalancing.

For indices, volatility clustering is particularly damaging. Even if fundamentals stabilize, elevated volatility suppresses multiples and delays recovery. Sustained rallies tend to emerge once volatility stops rising and begins to normalize, allowing risk to be rebuilt rather than forcibly reduced.

How These Forces Interact Across Market Phases

| Market Phase |

Dominant Driver |

Index Behavior |

| Early cycle |

Earnings acceleration |

Broad-based rallies |

| Mid-cycle |

Rates and growth balance |

Sector rotation |

| Late cycle |

Margins and yields |

Choppy, selective gains |

| Downturn |

Risk sentiment |

Sharp drawdowns |

| Recovery |

Positioning and volatility |

Fast rebounds |

Indices rarely respond to one driver in isolation. Late-cycle markets, for example, may see strong earnings but falling indices due to yield pressure and tight positioning. Understanding the interaction matters more than identifying the headline catalyst.

A Practical Example: What Really Moves the S&P 500

The S&P 500 is often treated as a proxy for the economy, but its price action is driven primarily by yields, earnings expectations, and positioning. Risk sentiment and volatility influence speed and magnitude, not direction.

US Treasury yields are the dominant short-term force. Rising real yields compress valuation multiples, especially for large-cap stocks with long-duration cash flows. When yields stabilize or fall, the same earnings outlook supports higher index levels through multiple expansion.

Earnings season influences the index through guidance and revisions, not headline results. The S&P 500 struggles when forward earnings estimates decline, even if reported profits beat expectations. Markets price the trajectory of earnings, not the last quarter.

Positioning determines how these forces translate into price moves. Crowded exposure and low volatility leave the index vulnerable to sharp pullbacks. Light positioning and falling volatility allow rallies to persist despite mixed fundamentals.

This is why the S&P 500 can rise during slowing growth or fall amid strong earnings. The clearest trends emerge only when yields, earnings expectations, and positioning align.

Why Indices Sometimes Ignore Bad News

Markets often appear irrational because they discount the future, not the present. When bad news arrives after positioning has already adjusted, indices may rise. Conversely, good data can coincide with market declines if expectations were already priced in.

This asymmetry explains why volatility and positioning are as important as fundamentals. Indices move most aggressively when expectations shift, not when information merely confirms consensus.

Risk Considerations

Regime shifts: Relationships between yields, earnings, and valuations hold only within a given macro and policy regime. Changes in inflation dynamics, central bank behavior, or financial conditions can break established correlations.

Positioning risk: Crowded exposure and low volatility create asymmetric downside. Even minor shocks can trigger rapid deleveraging, pushing indices lower without a corresponding deterioration in fundamentals.

Earnings risk: Margin pressure is often nonlinear. Costs can rise, and pricing power can fade quickly, forcing abrupt earnings revisions before revenue weakness becomes visible.

Liquidity and volatility risk: Rising volatility reduces market depth, widens spreads, and accelerates mechanical rebalancing. In these environments, price action can temporarily detach from valuation logic and amplify drawdowns.

Timing risk: Markets often reprice expectations ahead of economic or earnings data. Waiting for confirmation can mean reacting after the adjustment has already occurred.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. What moves indices most on a day-to-day basis?

In the short term, yields and positioning dominate. Changes in rate expectations reset valuation assumptions, while positioning determines whether markets absorb those shifts smoothly or react with outsized moves.

2. Why do indices react more to yields than to economic data?

Because yields directly affect discount rates. Even strong economic data can pressure indices if it pushes yields higher and tightens financial conditions faster than earnings expectations adjust.

3. How does earnings season actually move indices?

Indices respond to forward guidance, margins, and earnings revisions rather than headline beats. Markets price the future earnings path, not the most recent quarter’s results.

4. Why do indices sometimes sell off without negative news?

Crowded positioning and low volatility create fragility. When expectations are fully priced, even minor catalysts can trigger rapid deleveraging and sharp index declines.

5. Which S&P index is best for beginners to trade?

For most beginners, the S&P 500 is the most suitable index. It offers deep liquidity, tight spreads, and broad diversification across sectors, making price behavior more stable and easier to analyze than narrower or leveraged indices.

Conclusion

Stock indices function as complex, adaptive systems rather than simple reflections of economic headlines. Rates define valuation boundaries, earnings supply fundamental gravity, positioning governs market mechanics, sentiment channels capital flows, and volatility dictates both speed and fragility. Any framework that neglects one of these forces risks misreading price behavior.

Investors who grasp how these drivers interact gain a clearer lens for interpreting index moves across market phases. Markets rarely reward single-factor narratives. Indices advance with conviction when these forces align and lose coherence when they diverge.

Disclaimer: This material is for general information purposes only and is not intended as (and should not be considered to be) financial, investment or other advice on which reliance should be placed. No opinion given in the material constitutes a recommendation by EBC or the author that any particular investment, security, transaction or investment strategy is suitable for any specific person.