Every December, the same question comes back across trading desks: "Do we still get the January Effect, or is it just a nice story?" The honest answer is that the "easy" version of the trade has faded, but the underlying behaviour that created it has not disappeared.

Regardless, the "January Effect" is one of the cleanest stories in market folklore: Beaten-down stocks, especially small caps, are often sold for tax reasons into year-end, then rebound in January as that pressure fades and new money comes in. It's a simple, tidy story, and sometimes it does play out.

However, if you treat the January Effect as a guaranteed market-wide rally, you will be disappointed. If you treat it as a small-cap, beaten-down stock rebound window tied to year-end flows and thin liquidity, it still shows up often enough to matter, especially when you combine it with clean technical levels and risk control.

What Is the January Effect and What Is It Not?

The January Effect is a seasonal pattern in which stocks, particularly smaller companies, tend to deliver unusually robust returns in January compared with other months.

The classic setup has three moving parts:

Forced selling into late December: tax-loss selling and "cleaning up" portfolios.

A liquidity flip after the calendar turns: new allocations, bonuses, fresh risk budgets.

Mean reversion in the ugliest names: small caps and prior-year losers bounce hardest.

Academic studies going back decades have found that the effect is not evenly distributed across the month. For example, Rozeff and Kinney's classic work documented that monthly returns differed across the year, with January standing out as unusually strong.

Additionally, a significant portion of the "January premium" usually emerges in the first week of trading, occasionally even on the very first day, leading to crucial implications for timing and risk.

Lastly, the January effect is not the same thing as:

The Santa Claus Rally (late December into early January).

The January Barometer ("as goes January, so goes the year").

What the Long-Term Data Says

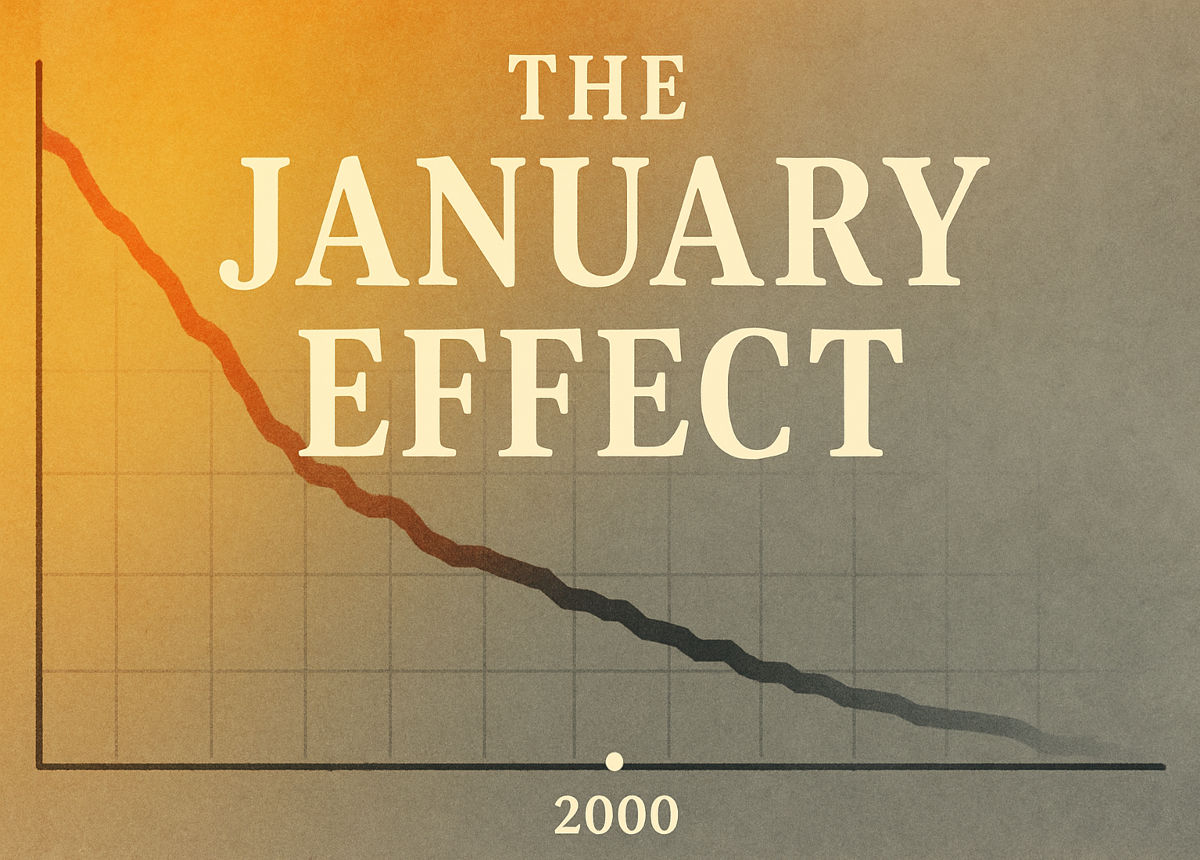

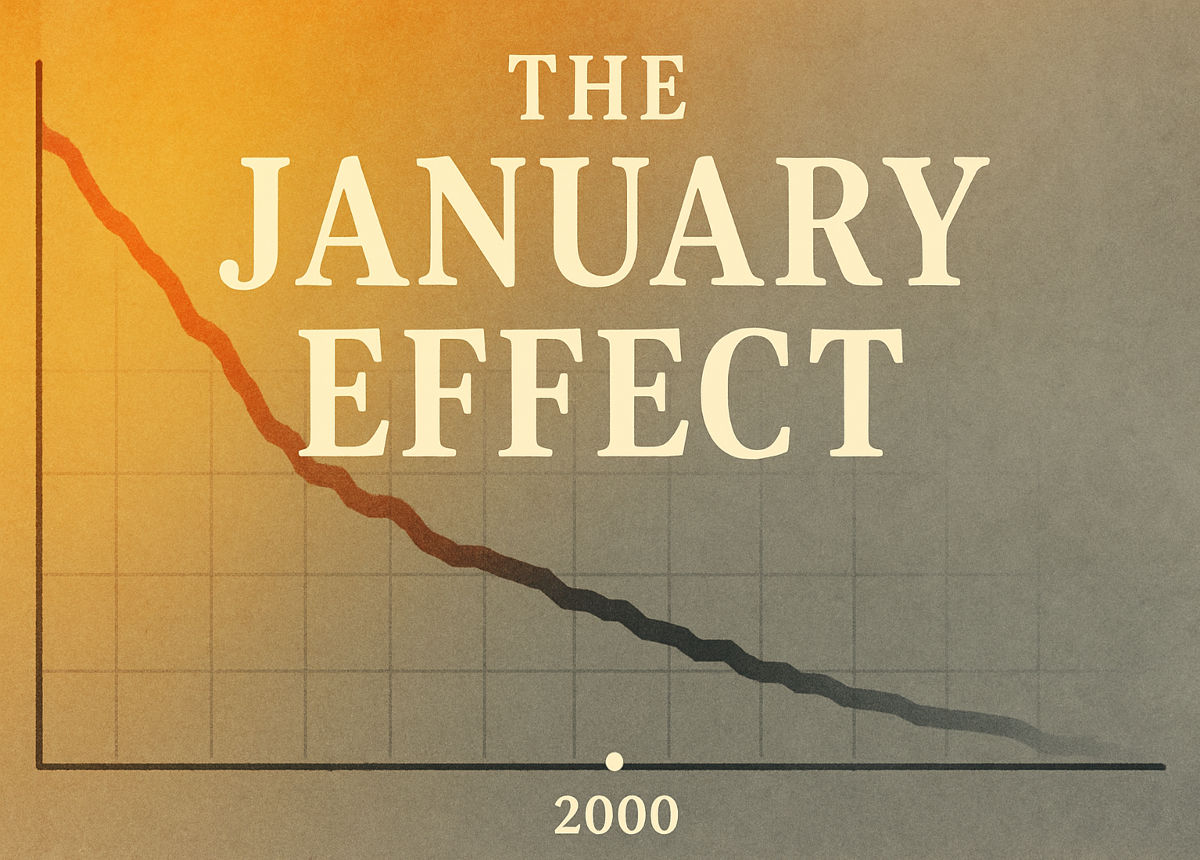

Historically, January is strong. But the edge has not been stable.

Historical split shows how stark the change can look:

| Period |

Large-cap avg January return |

Small-cap avg January return |

| 1928–2000 (large caps) / 1979–2000 (small caps) |

1.7% |

3.2% |

| 2000–2023 |

-0.3% |

0.1% |

However, it is not "gone forever," but it's a big warning sign: the simple calendar trade has been arbitraged and diluted.

Furthermore, January being "often strong" doesn't mean it's always the best month. One long-run summary shows January was the top month only 14 times in 97 years for large caps and eight times in 46 years for small caps.

So if you're looking for a guaranteed seasonal tailwind, the data does not support that.

What Historical Data Shows For the Broad Market?

| Measure |

Result |

| Average January return (S&P 500, since 1950) |

+1.07% |

| What that implies |

January has a positive drift, but not a guaranteed rally |

If you look at the S&P 500 alone, January is positive on average, but it is not the "best month" story many people assume.

Month-by-month studies of S&P 500 returns since 1950 show January's average return at +1.07%. That is a decent month, but it is not a magic button.

Thus, the key point is simple. The broad-market January Effect remains modest, heavily skewed by earlier decades when seasonal anomalies were simpler to exploit.

What Is the Real January Effect?

Where the January Effect earned its reputation was not with large caps. It was small caps and depressed stocks.

Summarised long-run data showing that from 1928 to 2000, January averaged about +1.7% for the S&P 500 and +3.2% for small caps, which is the classic "small beats large" signature.

Additionally, the effect has diminished since 2000, with January returns turning weak or even negative overall at times. That is a blunt warning: if you buy "January" without filtering for the right stocks, the edge is thin.

Does the January Effect Still Work?

| Market segment |

What history suggests |

Does it "still work"? |

| Broad large caps |

January has a positive average, but the anomaly is weaker |

Sometimes, but not reliably |

| Small caps |

Historically stronger January lift |

More often, especially early January |

| Biggest losers |

Tends to bounce after year-end selling |

Still shows up in pockets |

In summary, it remains noticeable but lacks clarity.

Look at the last couple of years around the turn:

January 2024: small caps fell -3.89% and lagged large caps by 528 basis points. That's the opposite of the classic story.

January 2025: both large caps and small caps gained about 2.7% and 2.5%, respectively. That's a "rising tide" month, not a special small-cap edge.

This is why you should stop asking "Is January bullish?" and start asking "Is there forced selling to unwind, and is risk appetite healthy enough to buy what got dumped?"

The Modern Reality: It Shifted From "January" to "Turn-Of-The-Year"

If you trade this like a calendar rule, you're already late.

Seasonal patterns suggest that small-cap outperformance often begins in mid-December rather than January, with much of the relative move typically completed by early spring.

That matches how markets behave now: traders anticipate the play, position early, and the "effect" becomes a window, not a month.

So the modern framing is:

Turn-of-the-year effect (mid-December to early January)

Most concentrated in the first week

Strongest in prior losers and illiquid pockets

Highly sensitive to rates, credit conditions, and risk appetite

Why Did the January Effect Weaken?

Markets learn. When enough people chase the same edge, it gets squeezed.

The data indicate that the January Effect has considerably diminished since the 1990s and should be regarded as merely one factor, rather than a separate strategy.

Three practical reasons explain most of the fade:

Better information and faster execution (easy edges get arbitraged).

More passive investing (flows are less "calendar sensitive" at the margin).

Broader tax optimisation tools (tax-loss harvesting can be done more systematically).

The edge did not vanish. It gravitated toward narrower corners: small, illiquid, and heavily sold names.

Current Large-Cap and Small-Cap Technical Analysis: Key Levels Into Early 2026

| Metric |

Large Cap ($SPX) |

Small Cap 2000 |

| Last |

6,878.49 |

2,558.78 |

| RSI (14) |

66.02 |

59.64 |

| MACD |

18.97 |

8.97 |

| MA5 |

6,876.54 |

2,563.99 |

| MA50 |

6,815.17 |

2,533.64 |

| MA200 |

6,787.07 |

2,472.67 |

| Classic S1 |

6,868.80 |

2,557.57 |

| Pivot |

6,873.89 |

2,560.26 |

| Classic R1 |

6,879.23 |

2,563.43 |

| 52W Low |

4,835.04 |

1,732.99 |

| 52W High |

6,920.34 |

2,595.98 |

How to Interpret the Table?

1) Large Caps Are Extended, but Not Broken

RSI in the mid-60s signals momentum is still firm, not a blow-off. The primary risk isn't an "overbought" condition, but rather a failed breakout.

Should the price fail to remain above the pivot area around $6,874, declines toward the $6,815–$6,787 moving-average range are more probable.

2) Small Caps Are Closer to the Decision Point

Small caps are pressing the upper end of their 52-week range. That creates two clean scenarios:

Break and hold above $2,596: opens room for continuation, and seasonality can help.

Reject near highs: the trap is fast because positioning into year-end is usually crowded.

With the MA200 near $2,473, that zone is the "line in the sand" for swing traders if the turn-of-the-year bid fades.

3) Watch Volatility for Timing

When VIX is near $14, dips tend to get bought quickly. If VIX starts climbing while price stalls near resistance, seasonality loses its support.

What Traders Can Do in the Upcoming "January Effect" Without Falling for the Myth?

For Beginners

Treat seasonality as a bias, not a signal.

Focus on risk management: entries near support, exits near resistance.

Don't chase the first green candles of January. The "first-week pop" can reverse fast.

For Intermediate Traders

The better trade is often relative strength: small caps versus large caps, not "market up."

Look for confirmation through improving breadth, steady volatility, and small-cap holdings above key moving averages.

For Advanced traders

The cleanest edge is often in dispersion: Previous underperformers and illiquid stocks are rebounding as the index appears stable.

Be selective. With evidence of stress in the smallest companies, "small cap beta" can hide landmines.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1) What Is the January Effect in Stocks?

It's the idea that stocks, especially small caps and prior losers, tend to outperform in January due to year-end selling pressure lifting and new money entering markets.

2) Does the January Effect Still Work Today?

Yes, but it is not as broad or as reliable as it once was.

3) Is January Always a Good Month for the S&P 500?

No. January's long-run average is positive, but it is not guaranteed like the myths. Since 1950, the S&P 50's average January return is about +1.07%.

4) How Should Traders Use the January Effect Today?

Use it as a filter, not a forecast. Focus on small caps and laggards, wait for technical confirmation, and manage risk tightly because these moves can reverse quickly.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the January Effect is not dead, but it's not a calendar cheat code either. Long-run data show the simple "buy in January" rule weakened sharply after 2000. The remaining edge tends to be brief, premature, and selective, often tied to the unwind of forced selling and shifts in liquidity.

For traders, the best way to approach the January Effect is to treat it like a time window plus a levels game. First, identify your invalidation level (key support), then look for price acceptance above the resistance. If the breakout fails and volatility rises, step back. Seasonality is helpful, but price always has the final say.

Disclaimer: This material is for general information purposes only and is not intended as (and should not be considered to be) financial, investment or other advice on which reliance should be placed. No opinion given in the material constitutes a recommendation by EBC or the author that any particular investment, security, transaction or investment strategy is suitable for any specific person.