Liquidation Definition

Liquidation is the formal process of closing a company and converting its assets into cash to pay creditors. It typically occurs when a business can no longer meet its financial obligations or when its liabilities exceed its assets. Once liquidation begins, the company ceases normal trading and moves towards legal dissolution.

The primary objective of liquidation is to realise assets and distribute proceeds fairly among creditors according to legal priority. A licensed insolvency practitioner is appointed as liquidator to manage the process, oversee asset sales, and ensure compliance with statutory duties.

Liquidation may be initiated voluntarily by directors and shareholders or enforced by a court following a creditor petition. Regardless of how it begins, liquidation marks the end of the company as a legal entity once the process is complete.

Types of Liquidation

Liquidation is categorised by the financial status of the company and the manner in which the process is initiated.

A creditors’ voluntary liquidation occurs when directors acknowledge that the company is insolvent and cannot continue trading. Shareholders pass a resolution to wind up the company and appoint a liquidator, often following professional advice.

A members’ voluntary liquidation applies to solvent companies that choose to cease operations. Directors must formally declare that the company can pay all debts in full, usually within twelve months. This form of liquidation is commonly used for corporate restructuring or retirement planning.

Compulsory liquidation takes place when a creditor applies to the court for a winding-up order, usually after unpaid debts such as trade invoices or loans. If the court is satisfied that the company is insolvent, liquidation is ordered, and an official liquidator is appointed.

Key Participants in Liquidation

Several parties play important roles throughout the liquidation process. Directors are responsible for recognising insolvency risks and initiating action. Shareholders approve resolutions in voluntary liquidations. Creditors submit claims and may influence decisions through voting rights. The liquidator controls the company once appointed and acts in the interests of creditors as a whole.

The liquidator’s duties include safeguarding assets, investigating past transactions, reporting misconduct where appropriate, and distributing funds in accordance with insolvency law.

The Liquidation Process Explained

Liquidation begins with a formal decision or court order. Once the liquidator is appointed, control of the company transfers away from directors. Trading usually stops unless limited activity is required to preserve asset value.

The liquidator identifies all company assets and arranges their sale. This may include property, inventory, machinery, vehicles, investments, and intellectual property. Sales are conducted to achieve a reasonable value under the circumstances.

Creditors are invited to submit proof of debt. Claims are reviewed and accepted or rejected. Once assets are realised, distributions are made based on statutory priority rules. After distributions are completed, final reports are issued, and the company is dissolved.

Creditor Priority and Recoveries

Not all creditors are treated equally in liquidation. Secured creditors with fixed charges over assets generally have the strongest claims and are paid first from the proceeds of those assets. Preferential creditors, including employees with unpaid wages up to statutory limits, are paid next.

Floating charge holders and unsecured creditors follow. Shareholders are paid only if all creditor claims are fully satisfied. In many liquidations, unsecured creditors recover only a small percentage of what they are owed, if anything at all.

Directors’ Duties and Risks

When a company approaches insolvency, directors’ responsibilities shift from shareholders to creditors. Continuing to trade while insolvent can result in personal liability. The liquidator reviews the director's conduct, financial decisions, and asset transfers made before liquidation.

If wrongful trading, fraudulent trading, or transactions at undervalue are identified, the liquidator may pursue legal action. Directors may also face disqualification if misconduct is proven.

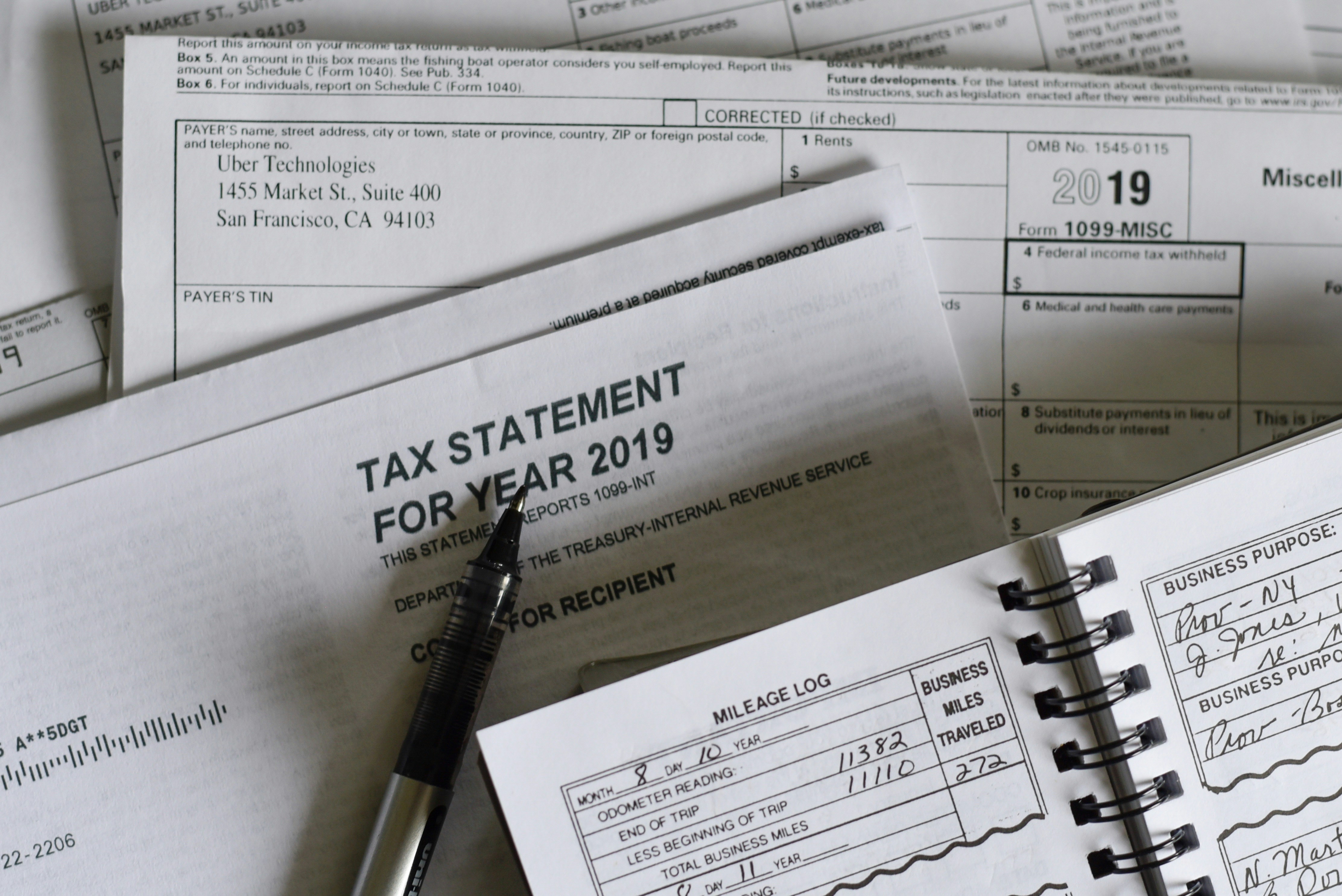

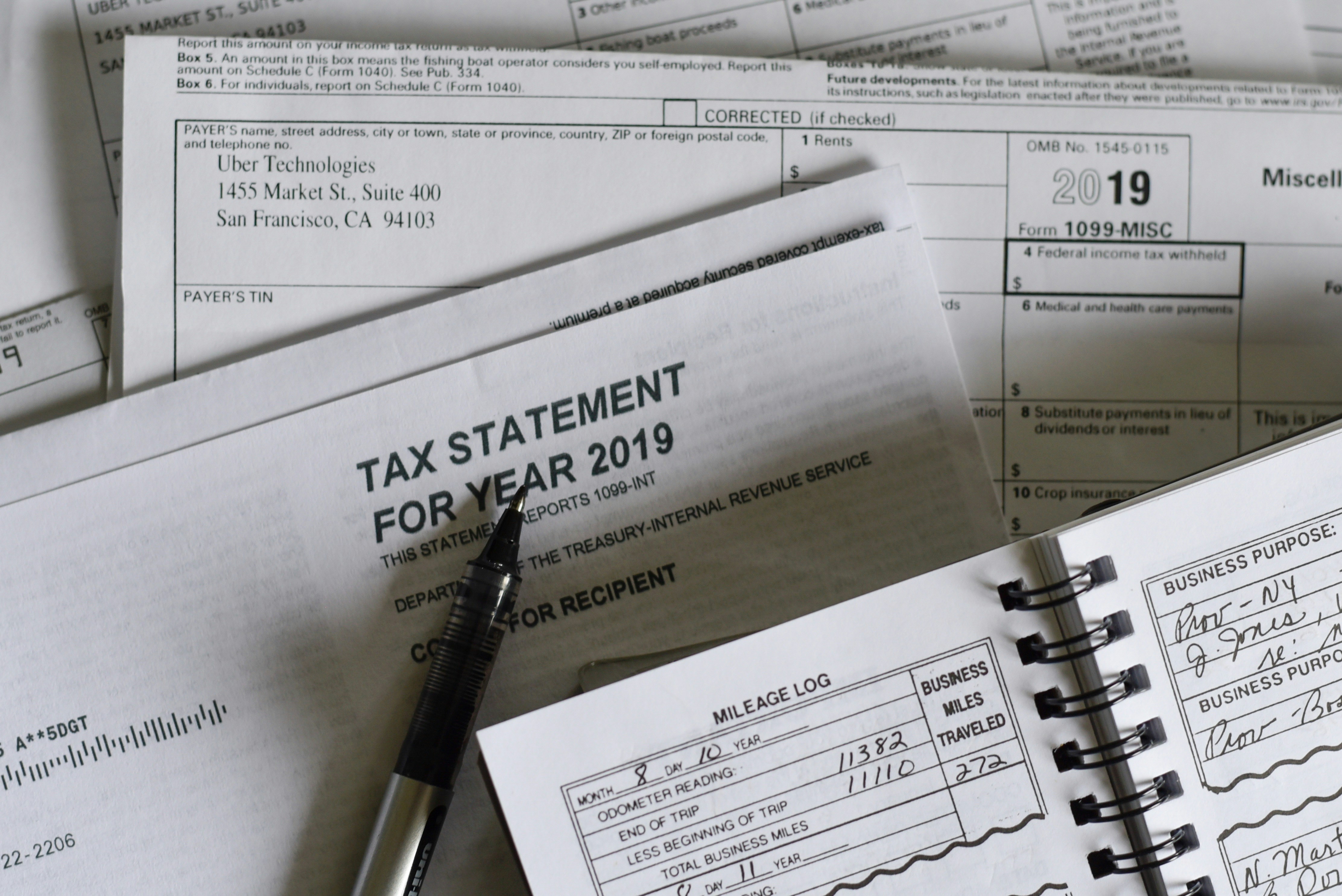

Tax Implications of Liquidation

Liquidation involves settling outstanding tax liabilities, including corporation tax, VAT, and payroll obligations. The liquidator liaises with tax authorities and ensures final filings are completed.

For shareholders, distributions received during liquidation may be subject to capital gains tax rather than income tax, depending on circumstances. Members’ voluntary liquidation is often used as a tax-efficient exit strategy, but professional advice is essential to ensure compliance.

Liquidation in Financial Markets

Liquidation also has a distinct meaning in financial markets. In trading, liquidation refers to the closing of positions by selling assets, either voluntarily or forcibly, to meet margin requirements or reduce exposure.

In leveraged trading, brokers may liquidate positions automatically when losses reduce account equity below required thresholds. This protects the broker and maintains market stability. Market liquidations often occur rapidly during periods of high volatility.

Large-scale liquidations can amplify price movements. Forced selling can push prices lower, triggering further margin calls and additional liquidations across the market.

Asset Liquidation and Valuation

Asset liquidation focuses on converting assets into cash, often under time pressure. As a result, liquidation value is typically lower than market value or book value.

Liquidation value reflects distressed sale conditions rather than long-term earning potential. It is an important metric for creditors assessing recovery prospects and for auditors evaluating whether a business can continue as a going concern.

Understanding liquidation value helps directors determine solvency and make informed decisions before financial distress worsens.

Employee Rights During Liquidation

Employees are directly affected when a company enters liquidation. Employment contracts usually terminate, and outstanding wages, holiday pay, and redundancy entitlements become claims against the company.

Employees often rank as preferential creditors up to statutory limits. Where company assets are insufficient, government-backed schemes may provide partial compensation. Claims above protected limits are treated as unsecured and may not be fully recovered.

Cross-Border Liquidation

Cross-border liquidation arises when a company operates in multiple jurisdictions. Assets, creditors, and legal proceedings may be spread across different countries, complicating the process.

International insolvency frameworks aim to facilitate cooperation between courts and liquidators. These arrangements help recognise foreign proceedings and coordinate asset recovery, reducing duplication and conflict.

Without cooperation, cross-border liquidation can be slow and costly, reducing returns for creditors.

Economic Significance of Liquidation

Liquidation affects more than the company involved. Suppliers, employees, and local economies can experience knock-on effects. High liquidation rates may signal economic stress, reduced access to credit, or declining consumer demand.

At the same time, liquidation plays a vital role in market economies by reallocating resources from unviable businesses to more productive uses. This process supports long-term economic efficiency and renewal.

Pro Tips

Directors should seek professional advice as soon as financial difficulties arise. Early action can preserve value and reduce personal risk. Exploring alternatives such as restructuring or administration may avoid liquidation altogether.

Creditors should understand their ranking and security position. Active engagement with the liquidator improves transparency and ensures claims are properly assessed.

FAQ Section

1. What triggers liquidation?

Liquidation is triggered when a company becomes insolvent, chooses to cease operations, or faces a court order following a creditor petition. Directors must act once they know the company cannot meet its financial obligations to avoid legal consequences.

2. Can directors be personally liable during liquidation?

Yes. Directors may face personal liability if they continue trading while insolvent, breach fiduciary duties, or engage in wrongful or fraudulent trading. The liquidator investigates conduct before and during insolvency.

3. Do shareholders receive money in liquidation?

Shareholders receive distributions only after all creditor claims are paid in full. In most insolvent liquidations, there are insufficient assets for shareholders to accept any return.

4. How long does liquidation take?

Liquidation can take several months or several years. The duration depends on asset complexity, disputes, creditor numbers, and whether legal actions are required to recover funds.

5. How is liquidation different from bankruptcy?

Liquidation applies to companies and involves winding up a legal entity. Bankruptcy applies to individuals and follows a different legal framework, although both aim to resolve insolvency and distribute assets fairly.

Summary

Liquidation is a structured legal process designed to close a company, realise its assets, and distribute funds to creditors in an orderly manner. While often seen as a last resort, it serves an essential role in both business law and financial markets. By understanding liquidation, its implications, and alternatives, stakeholders can make informed decisions and manage risk more effectively.

Disclaimer: This material is for general information purposes only and is not intended as (and should not be considered to be) financial, investment, or other advice on which reliance should be placed. No opinion given in the material constitutes a recommendation by EBC or the author that any particular investment, security, transaction, or investment strategy is suitable for any specific person.