A bull market is not “prices going up,” and a bear market is not “prices going down”, because those labels hide important distinctions: magnitude (how far prices fall), duration (how long it lasts), root cause (credit crisis, policy shock, pandemic, valuation collapse), and aftereffects (policy changes, structural realignment).

Learn how bull markets are built and bear markets unfold, not as abstract labels but as reproducible patterns, by studying real market examples.

After this article, you’ll be able to (1) name the dominant drivers of each cycle, (2) recognize early warning signals, and (3) choose a defensible strategy for each market regime.

Quick Definitions

Bull market: a sustained rise in broad-market prices, typically measured as a 20%+ gain from a prior trough (practical definition varies by context).

Correction: a drop of 10-20% from a recent high.

Bear market: a fall of 20% or more from a recent peak; severity and duration vary widely. These are the operative, market-standard definitions used by analysts and major data providers.

Simple Tests That Usually Gets It Right

1. The 20% Rule Is A Label, Not A Diagnosis

The 20% threshold is helpful for headlines, not for strategy. A decline can be fast and event-driven, or slow and valuation-driven.

The difference matters because recoveries, leadership, and volatility behave differently depending on the cause. A trader or investor who only uses “down 20%” misses the real question: What is being repriced?

2. Price Moves Come From Two Dials: Earnings And The Discount Rate

Equity prices can be simplified as:

Bull markets are usually a mix of (1) earnings growth and (2) multiple expansion (investors paying more per $1 of profit). Bear markets usually involve (1) multiple compression, (2) earnings falling, or (3) both at once.

The “discount rate” is the financial gravity that pulls valuations down when interest rates rise or when risk premiums widen.

3. Contagion Is The Overlooked Tell

One of the cleanest ways to spot a serious bear market is whether weakness stays contained or spreads across sectors.

Research from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis highlights that some bubbles burst with limited spillover, while others drive broad movement such as markets “moving together” as stress jumps from one area to the entire system.

When correlations rise and everything sells off together, it often signals funding stress, forced selling, or a hit to the financial system’s plumbing, not just a valuation reset in one corner of the market.

Real World Example

1) 1987 - Black Monday (Crash Without a Bear Market)

On October 19, 1987, the Dow Jones Industrial Average dropped 22.6% in one session, still cited as the largest one-day percentage decline in its history. The episode was amplified by market structure issues and feedback loops in trading, not by a collapsed economy.

Magnitude & duration:

The key lesson is recovery speed: the Federal Reserve History summary notes that markets regained a large portion of losses quickly, and U.S. stock markets surpassed their pre-crash highs in less than two years. That is the signature of a liquidity/structure shock, violent, then repairable when the system keeps functioning.

2) 2000-2002 - Dot-Com Bear Market (Valuation Implosion)

The early-2000s downturn is the classic “multiple compression” bear: prices fell because expectations were too high relative to cash flows and realistic growth. In simple terms, investors had paid too much for future profits that did not arrive on schedule.

Magnitude & duration:

The Nasdaq Composite fell roughly 78% from its peak to its trough during the unwind, making it a clear case study in how concentrated leadership can cut both ways: when the same sector dominates an index on the way up, it can dominate the damage on the way down.

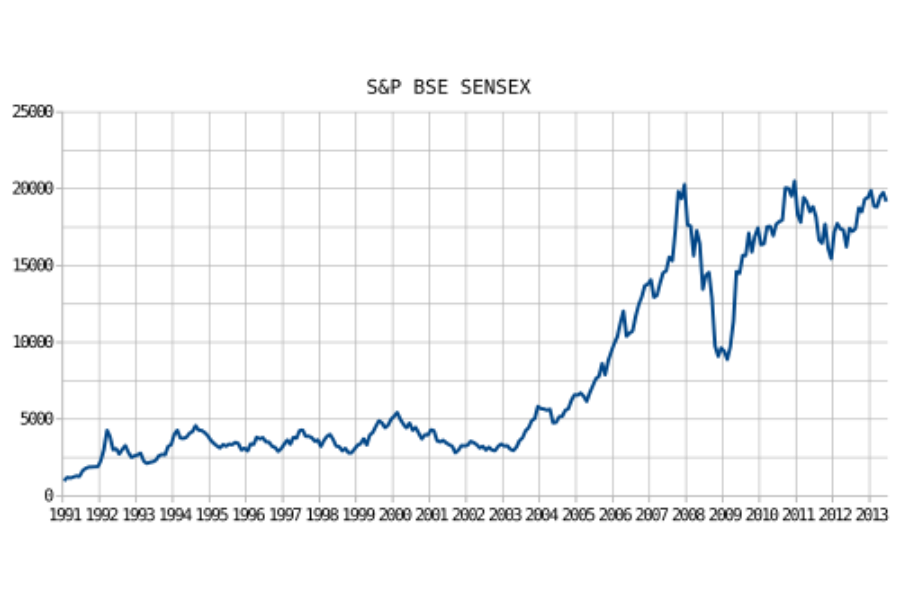

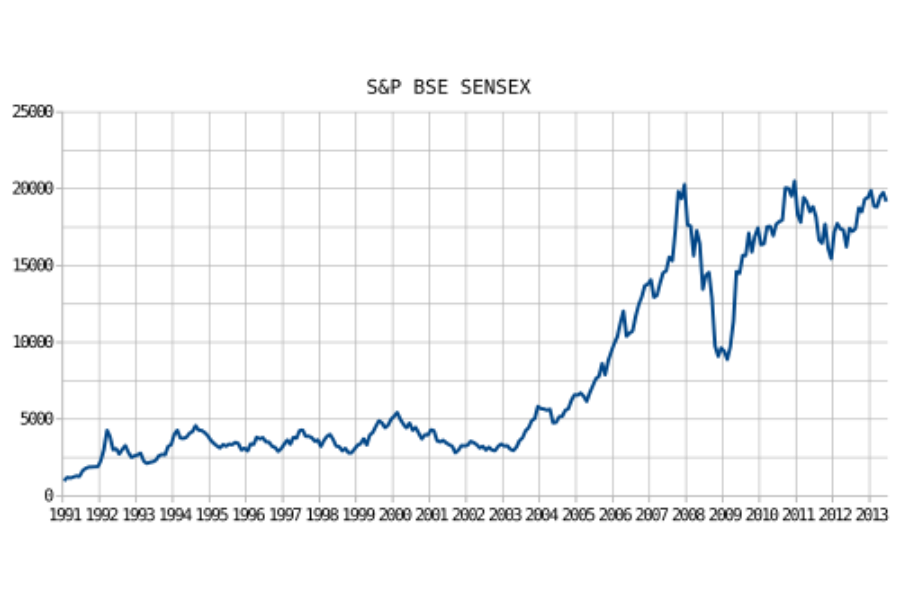

3) 2007-2009 - Global Financial Crisis (Credit-Driven Bear)

The Global Financial Crisis was not mainly about overpaying for earnings; it was about leverage, credit quality, and interconnected balance sheets.

Federal Reserve History notes that home prices fell about 30% on average from their mid-2006 peak to mid-2009, while the S&P 500 fell 57% from its October 2007 peak to its trough in March 2009.

Magnitude & duration:

This is what “contagion” looks like: housing stress hit lenders, lenders hit funding markets, and the whole system repriced risk. The policy response also illustrates the playbook for systemic stress: the federal funds rate was cut aggressively and unconventional tools were introduced as the lower bound approached.

4) 2020 - COVID-19 Crash (Exogenous Shock Bear)

The 2020 selloff shows how quickly markets can drop when uncertainty is extreme; and how quickly they can recover when liquidity backstops are credible.

Analysis from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis notes that after peaking on February 19, 2020, the S&P 500 fell to about 66% of its peak by March 23, roughly a 34% drawdown.

Magnitude & duration:

What makes 2020 distinct is the rebound pace. An S&P Dow Jones Indices report describing 2020 notes that the S&P 500 regained its all-time high by August.

For traders, it is also a reminder that volatility can spike to historic levels during shock events, such as the VIX reaching an all-time closing high of 82.69 in March 2020.

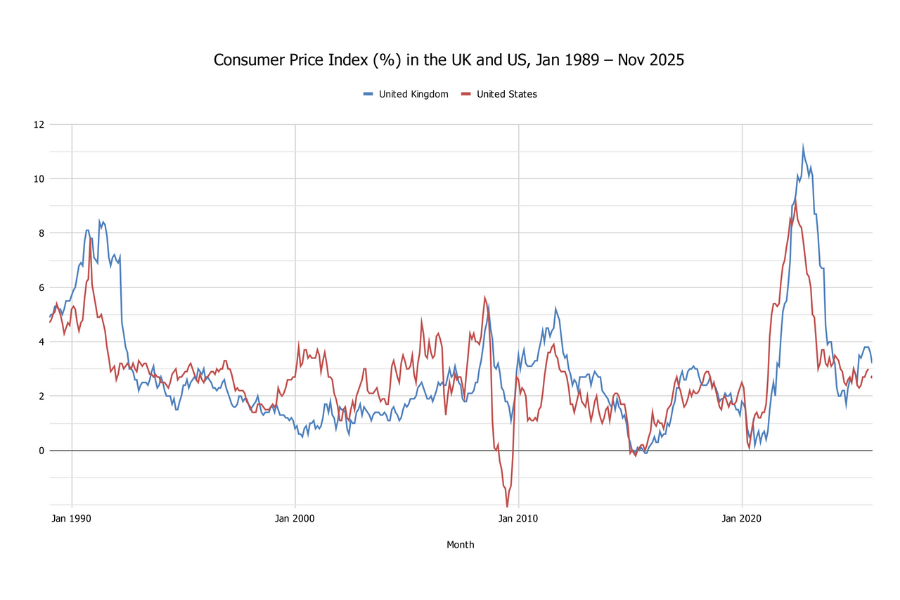

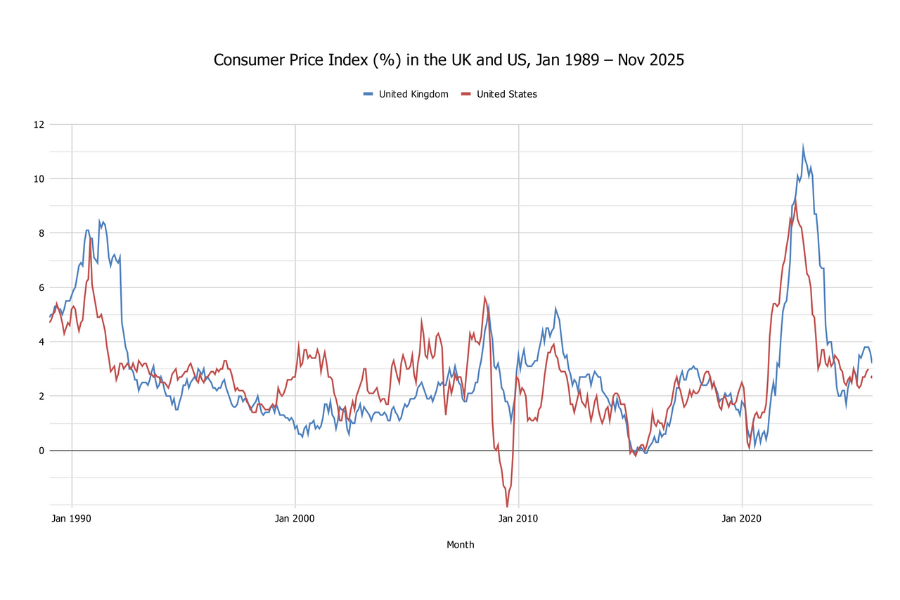

5) 2022 - Inflation & Rate-Hike Bear Market (Policy-Driven)

The 2022 decline is the cleanest recent example of a bear market driven primarily by inflation and interest rates. U.S. inflation reached 9.1% year-over-year in June 2022 (CPI-U), the largest 12-month increase since the period ending November 1981.

Magnitude & duration:

As inflation stayed elevated, the Federal Reserve raised the target range for the federal funds rate rapidly from near-zero conditions to restrictive territory. The Federal Reserve’s official record of the target range changes shows the step-up in 2022 and beyond.

Aftermath (2023-2025):

2023-2024: Strong AI-led bull market, concentrated in mega-cap tech

2025: Markets characterized by selective bull behavior, higher dispersion, and sensitivity to rates and earnings quality

A St. Louis Fed analysis noted that the real return on stocks, measured by the S&P 500 Index, was about -25% for the year through October 2022, consistent with a large repricing of long-duration growth cash flows when discount rates rise.

What Differs Between Bulls And Bears

A regime-based analytical framework

Bull and bear markets are not simply up or down phases. They are distinct market regimes, each governed by different mechanics, behaviors, and policy dynamics. Understanding these differences is essential for investors, traders, and risk managers.

| Market Regime Type |

Usual Trigger |

Early Clues |

What Typically Stabilizes It |

Historical Example |

| Liquidity / Structure Shock |

Market plumbing issues, positioning stress, thin liquidity |

Sudden gap moves, failed liquidity, rapid policy reassurance |

Liquidity support, market structure reforms |

1987 |

| Valuation Reset |

Overextended multiples, narrative-led pricing |

Narrow leadership, speculative issuance, profitless growth |

Earnings reality combined with time |

2000–2002 |

| Credit / Balance Sheet Stress |

Excess leverage meets falling asset prices |

Widening credit spreads, funding stress, rising correlations |

Backstops, recapitalization, balance sheet repair |

2007–2009 |

| Exogenous Shock |

Sudden external or non-financial event |

Volatility spike, indiscriminate selling |

Coordinated policy response and clearer outlook |

2020 |

| Policy Tightening |

Inflation forces higher interest rates |

Multiple compression, long-duration underperformance |

Disinflation and stabilizing rate expectations |

2022 |

Bottom Line

Bull markets are confidence-driven expansions.

Bear markets are risk-repricing events.

Understanding which type of bear market you are in, rather than reacting to headlines, is the foundation of disciplined, professional market strategy.

Tactical Playbook For Traders And Investors

If you believe a bull will continue: favour cyclicals, growth, and higher beta with disciplined position sizing.

If you suspect a bear is starting: raise cash, reduce leverage, add high-quality bonds and cash equivalents, consider hedges (puts, inverse ETFs) or options collars.

For retirement/long-term investors: dollar-cost averaging and rebalancing across market cycles remains statistically robust.

For active traders: use volatility, breadth, and market internals (e.g., advancing vs declining issues) to confirm regime changes.

For institutions: stress-test balance sheets under deep drawdowns and ensure liquidity buffers.

Signals That Tend To Flip Before The Headlines

No single indicator “predicts” a bear market reliably, but regime shifts often leave footprints.

Market Breadth And Leadership: Narrow rallies can be fragile; broad participation is harder to break.

Cross-Asset Stress: If equities fall while credit spreads widen and liquidity thins, the odds rise that the issue is systemic rather than cosmetic.

Policy Expectations: When inflation surprises upward, valuation math changes quickly because discount rates rise. The 2022 CPI surge and rate path are a real-world example of that transmission.

Behavioral And Traps To Avoid

Assuming a correction is “over” because it’s short-lived (fast recoveries sometimes hide underlying structural damage).

Chasing top momentum (buying late in bubbles).

Over-reliance on a single indicator, combining macro, credit, valuation and technical signals.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. What is the main difference between a bull market and a bear market?

A bull market is a sustained rise in broad prices, usually supported by improving profits, easier financial conditions, or higher valuations. A bear market is a sustained decline where risk is being repriced, through falling earnings, lower valuations, or credit and liquidity stress.

2. Is every bear market accompanied by a recession?

No, not every bear market coincides with a recession, as some are driven by liquidity shocks or valuation adjustments without immediate economic contraction, while others, particularly credit-driven bears, do align closely with recessions.

3. How long do bear markets typically last?

Bear markets vary significantly in duration, ranging from weeks or months in fast, event-driven declines to multiple years in structural or credit-related downturns, as documented in historical summaries by Investopedia.

4. Can a market crash happen without a long bear market?

Yes. The 1987 crash was extreme in a single day, but markets recovered a large share of losses quickly and exceeded prior highs in less than two years. That pattern fits a liquidity/structure shock more than a long economic downturn.

5. Should investors sell everything when the market drops 20%?

Selling everything after a 20% decline is not automatically the correct decision, as the appropriate response depends on an investor’s time horizon, risk tolerance, diversification, and the underlying cause of the market decline.

6. Why do bear markets feel more severe than bull markets feel rewarding?

Bear markets feel more severe because losses trigger stronger emotional reactions than equivalent gains, while rising volatility, higher correlations, and negative narratives amplify the psychological impact of declines.

7. What is the most important lesson investors should learn from bear markets?

The most important lesson is that bear markets function as reset mechanisms that reprice risk, reduce excess leverage, and create the conditions necessary for future bull markets.

Summary

Bull and bear markets represent different market regimes, not just rising or falling prices. Bull markets typically build gradually on earnings growth, supportive liquidity, and improving confidence, while bear markets involve rapid risk repricing driven by valuation excesses, credit stress, policy tightening, or external shocks.

Bear markets differ widely in speed and duration, and their severity is often shaped by the policy response. Investor behavior amplifies both phases; optimism and leverage extend bull markets, while fear and forced selling intensify bear markets.

The key takeaway is that successful investing depends less on reacting to market moves and more on understanding which regime is in place. Recognizing the underlying drivers of a market cycle allows investors to manage risk more effectively and make more disciplined, long-term decisions.

Disclaimer: This material is for general information purposes only and is not intended as (and should not be considered to be) financial, investment or other advice on which reliance should be placed. No opinion given in the material constitutes a recommendation by EBC or the author that any particular investment, security, transaction or investment strategy is suitable for any specific person.