Long-Term Capital Management (LTCM) serves as a prominent case study illustrating how ostensibly low-risk trades can become existential threats when financed with excessive leverage. The fund’s primary strategies did not involve directional bets on interest rates or equities. Instead, LTCM focused on relative value positions intended to capture small returns as prices converged.

However, in 1998, an abrupt market regime shift transformed convergence into divergence, and funding mechanics exacerbated the situation. The key lesson for traders is not the inadequacy of models, but rather that liquidity constraints, collateral requirements, and crowded trades can negate any valuation advantage during periods of market stress.

By late 1998, LTCM’s near-failure was so entangled with major dealers that the Federal Reserve Bank of New York helped coordinate a private-sector recapitalisation to reduce the risk of a disorderly liquidation and broader market disruption.

Key Takeaways

LTCM’s advantage was modest but highly scalable, employing $30 of debt for every $1 of capital by the end of 1997 to amplify small basis-point mispricings into substantial returns.

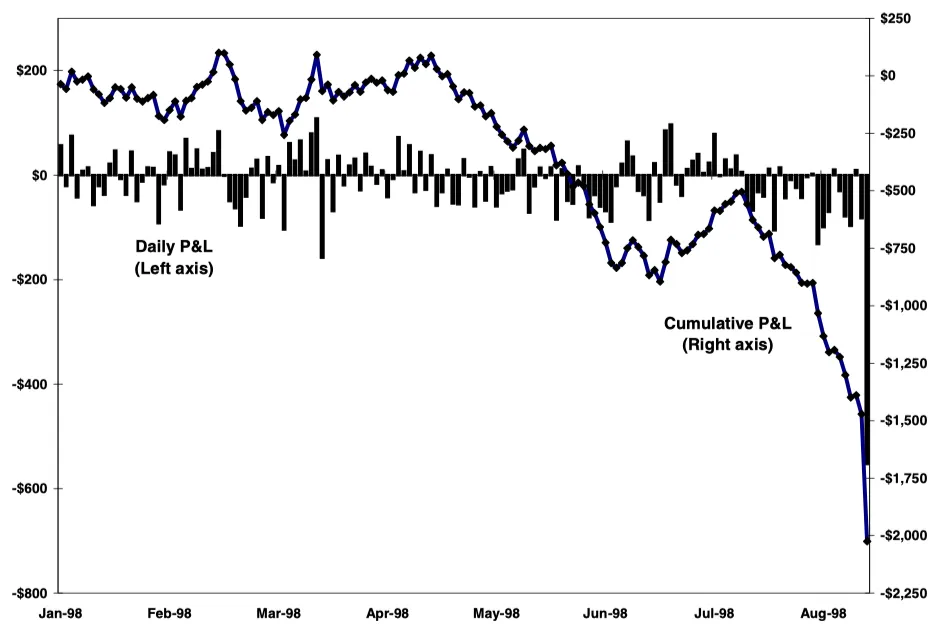

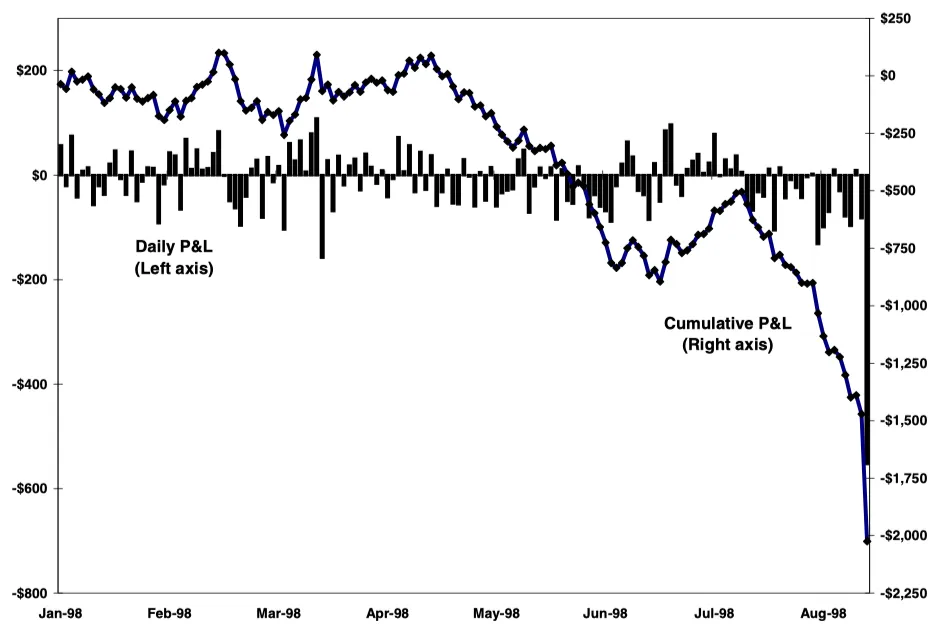

The macro catalyst was a flight-to-quality shock after Russia devalued and stopped payments on debt in August 1998, pushing spreads to diverge “in almost every case” and driving a 44 per cent loss in August alone.

The systemic risk was not just losses. It was position size, opacity, and interconnected counterparties, including vast OTC derivatives exposure.

The rescue was a private-sector recapitalisation of about $3.6 billion by 14 institutions, facilitated by the New York Fed, explicitly to prevent a destabilising fire sale.

Contemporary leveraged bond relative-value trades reflect the same vulnerabilities observed in the LTCM episode.

What Is LTCM

Long-Term Capital Management was founded in 1994 by John Meriwether, a prominent bond trader, and it quickly became a symbol of quantitative finance. The fund’s reputation was strengthened by its association with elite academic finance, and by early performance that looked unusually consistent: 20 per cent in 1994, 43 per cent in 1995, 41 per cent in 1996, and 17 per cent in 1997.

LTCM positioned itself as a market-neutral fund, implying that its returns were intended to be independent of overall market direction. In practice, this neutrality depended on a stable market environment characterized by liquid funding, predictable correlations, and spreads that, while occasionally widening, would ultimately revert to the mean.

The fund’s underlying business model centered on aggressive financing. LTCM borrowed extensively, maintained significant positions in interest rates and credit instruments, and utilized derivatives to exploit relative mispricings on a large scale.

The Convergence Machine: How LTCM Made Money

At its core, LTCM ran convergence trades. The logic is simple: two related instruments should trade at a stable spread because their cash flows are similar or because arbitrage links them. When the spread widens beyond “fair,” you buy the cheap leg and sell the rich leg, expecting convergence.

During stable market conditions, such strategies may appear to generate risk-free profits. However, under stressed conditions, they can lead to forced liquidations, as spreads may widen significantly beyond historical expectations and leveraged portfolios may encounter margin calls before convergence occurs.

Common structures in the LTCM playbook included:

Government bond relative value across countries and maturities, betting on small spread compression.

Swap spread and interest rate relative value via swaps and cash bonds, expressing curve and spread views without large outright duration risk.

Equity volatility exposure, including positions that effectively left the fund short volatility, is vulnerable to a sudden repricing of tail risk.

The critical point for traders is that convergence strategies often have short convexity. They tend to perform steadily until a liquidity shock forces spreads wider, volatility higher, and financing tighter simultaneously.

| Metric |

What it looked like |

Why it mattered |

| Annual returns (1994 to 1997) |

20%, 43%, 41%, 17% |

Built credibility, attracted capital, and supported higher leverage. |

| Balance-sheet leverage (end-1997) |

About 28-to-1 (assets to equity), often described as about $30 debt per $1 of capital |

Small spread moves produced large PnL swings and faster margin pressure. |

| Securities financed (Aug 31, 1998) |

About $125 billion |

Scale made exits market-moving, especially in stress. |

| OTC derivatives notional (end-1997) |

About $1.3 trillion |

Increased sensitivity to collateral terms and counterparty risk. |

| Number of trades (Aug 1998) |

Over 60,000 |

Complexity made rapid, clean deleveraging harder. |

Why The LTCM Fell

1) The Shock: Russia and the Global Flight to Liquidity

In August 1998, Russia devalued and suspended payments on parts of its debt, triggering a sharp flight to liquidity. Instead of converging, spreads across markets diverged, the opposite of LTCM’s core assumption, and the fund suffered a severe drawdown. This matters because traders often mislabel regime shifts as “temporary volatility.” In convergence portfolios, volatility is not noise; it is the mechanism that triggers margin calls and forced deleveraging.

This matters because traders often mislabel regime shifts as “temporary volatility.” In convergence portfolios, volatility is not noise. It is the mechanism that triggers margin calls.

2) The Mechanism: Leverage Turns Time Into the Enemy

LTCM’s trades may have been correct from a valuation perspective, but still failed due to financing constraints. As losses accumulated, the fund’s equity diminished, thereby increasing leverage. This rising leverage necessitated position reductions amid widening spreads, thereby crystallising losses.

| Indicator |

Approximate value |

Why it mattered |

| Leverage (end-1997) |

About $30 debt per $1 capital |

Small spread moves became lethal under collateral rules. |

| 1998 August performance |

About -44% in August |

The drawdown accelerated margin calls and forced selling. |

| Securities financed |

About $125 billion |

Exits became market-moving, widening spreads further. |

| Derivatives notional |

About $1.3 trillion |

OTC exposure amplified opacity and counterparty sensitivity. |

| Rescue package |

About $3.6 billion from 14 firms |

Designed to reduce the risk of a disorderly fire sale. |

The CFTC later summarised the scale bluntly: LTCM had invested in securities valued at around $125 billion and held derivatives with a notional amount of about $1.3 trillion, much of it OTC (over-the-counter). Even if “notional” is not the same as risk, it signals how sensitive the book was to collateral terms, margining, and counterparty behaviour under stress.

3) Crowding and Market Impact: When Everyone Runs the Same Play

Relative-value trades are attractive precisely because they appear repeatable. That also means they get crowded. When many funds, dealers, and desks hold similar spread bets, forced selling becomes correlated. Liquidity disappears where it is most needed, and “fair value” becomes irrelevant until balance sheets stabilise.

The New York Fed concluded the danger was a rapid, widespread fire sale if multiple counterparties tried to exit simultaneously. It was the systemic spillover risk, not sympathy for LTCM, that drove coordination.

4) Model Risk: VaR Is Not a Seatbelt in a Cliff Crash

LTCM’s models were sophisticated, but they lived in a world where historical distributions were informative, correlations were stable, and liquidity was available. The CFTC explicitly raised questions about internal controls and the limits of value-at-risk (VaR)- style frameworks when funding and OTC opacity interact.

Value-at-Risk (VaR) estimates potential losses based on historical market behavior. LTCM’s failure demonstrated that markets can, at times, deviate significantly from historical patterns.

The 1998 Rescue and the Policy Signal Traders Still Miss

On September 23, 1998, a consortium of 14 banks and broker-dealers injected about $3.6 billion to stabilise LTCM, with the Federal Reserve Bank of New York facilitating the process. The Fed did not lend public money, but its role signalled that non-bank leverage can become a public problem when it is wired into dealer balance sheets and core market plumbing.

The policy also moved. In late 1998, the Federal Reserve reduced the expected federal funds rate three times, totalling 75 basis points between late September and mid-November, amid unusual global and market strains. The point for traders is the transmission channel: a hedge-fund-centred liquidity event can spill into broader financial conditions quickly.

Lessons That Traders Can Learn From LTCM in 2026

1) Treat leverage as a volatility multiplier, not a return enhancer.

1) Treat leverage as a volatility multiplier, not a return enhancer.

When a trade offers an expected return of 5 to 15 basis points, the critical consideration is the magnitude of spread shock that can be withstood before financing constraints necessitate liquidation. It is essential to model the sequence: a widening spread increases Value-at-Risk, which tightens risk limits, triggers selling, and further widens spreads.

2) Price the funding leg every day.

In leveraged strategies, the funding leg is the position. Monitor repo terms, haircuts, collateral eligibility, and derivative margin dynamics as primary signals, not operational details.

3) Stress test for correlation going to one

Diversification based on calm correlations fails in crises. The stress test that matters is one in which multiple spreads widen together, liquidity evaporates, and hedges gap.

4) Avoid “hidden short volatility”

Many relative value portfolios are synthetically short volatility because they depend on mean reversion and stable liquidity. If volatility rises, spreads can widen, and margin requirements can expand simultaneously.

5) Assume crowding in trades that look “obvious”

If a strategy has become a talking point, it is probably on multiple balance sheets. Crowding is a structural risk factor. It does not show up in PnL until it does.

6) Define invalidation points and size to survive them.

Professional execution requires predefined levels at which the thesis is wrong, and the risk is cut. Treat this like engineering, not intuition, with explicit triggers and volatility-aware sizing.

7) Separate solvency from liquidity

LTCM was not “insolvent” on a long-horizon valuation argument. It was illiquid and over-levered under mark-to-market collateral rules. Traders who confuse these concepts will repeat the same mistake in modern instruments.

Why LTCM Still Matters: Modern Echoes in the Treasury Basis Trade and Beyond

1) The Treasury cash-futures basis trade: the 2020 warning shot.

The Treasury basis trade exploits small differences between cash Treasuries and Treasury futures, typically financed through repo. During the March 2020 dash-for-cash, evidence suggests basis-trade-heavy hedge funds faced greater margin pressure and liquidated exposures more aggressively, contributing to strains in market liquidity.

This is LTCM’s template: a relative value spread trade funded in short-term markets that works until volatility and collateral dynamics turn against it.

2) The UK LDI crisis in 2022: Leverage outside hedge funds can still behave like LTCM

In September 2022, UK gilts experienced extreme stress, amplified by leveraged liability-driven investment strategies that faced sudden collateral demands and were forced to sell gilts to raise cash. The Bank of England’s research ties the amplification to repo and derivative exposures and documents large-scale sales pressure during the episode.

Different institutions, same mechanism: leverage, margin calls, and forced selling combine to create a liquidity spiral.

3) 2025-2026: Leverage concentration is back in focus

Recent official research highlights how large Treasury relative-value positioning has become within parts of the hedge fund sector. A Federal Reserve note estimated that Cayman-domiciled hedge funds’ Treasury holdings reached $1.85 trillion by the end of 2024, and that official cross-border data may undercount these holdings by roughly $1.4 trillion due to repo-collateral reporting frictions.

BIS analysis adds scale: by Q2 2025, hedge funds’ long U.S. Treasury exposures totalled $2.379 trillion and short exposures $1.748 trillion, with about $1.060 trillion in short Treasury futures linked to the cash-futures basis trade. The BIS also estimates an implied upper-bound size of about $631 billion for a related swap spread trade in Q2 2025. The LTCM relevance is the same funding logic: small edges, scaled up, can turn into liquidity stress when volatility spikes and financing tightens.

That is the modern relevance of LTCM: The market continues to manufacture trades that earn small edges, then finances them with structures that can destabilise liquidity under stress. Regulators have responded with calls for better data and limits on leverage in parts of the non-bank sector, reflecting the same systemic-risk logic that surrounded LTCM.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1) What does LTCM stand for?

LTCM stands for Long-Term Capital Management, a hedge fund founded in 1994 that employed heavily leveraged relative-value and convergence strategies. It nearly collapsed in 1998 after spreads moved violently against its positions and funding conditions tightened.

2) When did the LTCM collapse?

LTCM’s collapse unfolded from late August to September 1998. The fund suffered its most dramatic hit in August 1998 as global spreads blew out after Russia’s shock, then spiralled toward failure through September. A private-sector rescue was organised on September 23, 1998, to prevent disorderly liquidation.

3) Did the Federal Reserve bail out LTCM with taxpayer money?

No public funds were lent to LTCM. The New York Fed facilitated a private-sector recapitalisation by 14 institutions, designed to prevent a disorderly liquidation that could have destabilised markets.

4) What exactly caused LTCM to blow up?

A macro shock and liquidity shock arrived together. Following Russia’s August 1998 default-related events, markets entered a flight-to-quality regime. Spreads diverged, LTCM suffered large mark-to-market losses, and leverage plus margin mechanics forced deleveraging at distressed prices.

5) What should traders monitor to avoid an LTCM-style liquidation?

Watch the variables that control survivability: volatility regimes, bid-ask and depth, repo terms and haircuts, margin requirements, crowded positioning, and correlation spikes. The earliest warning signs are usually in funding and liquidity, not valuation.

6) How is today’s Treasury basis trade similar to the LTCM trade?

The Treasury basis trade also targets small pricing differences and often relies on repo financing. Official and academic work links basis-trade-heavy funds to heightened margin pressure during stress periods like March 2020, echoing LTCM’s vulnerability to funding and collateral dynamics.

Conclusion

LTCM was not a story about bad math. It was a story about financing a fragile set of convergence bets with leverage so large that time stopped being an ally. Once Russia’s shock flipped the market into a liquidity-first regime, spreads widened, collateral demands rose, and liquidation risk became systemic because the positions were too large and too interconnected to unwind cleanly.

For traders in 2026, the relevance is immediate: relative-value strategies that harvest small edges in sovereign bond markets and derivatives still tend to rely on short-term financing. That structure can look stable for long periods, then break quickly when volatility rises, and collateral terms tighten.

Although financial instruments and reporting standards have evolved, the fundamental lesson of Long-Term Capital Management persists: markets can remain irrational for longer than a leveraged portfolio can remain solvent.

Disclaimer: This material is for general information purposes only and is not intended as (and should not be considered to be) financial, investment, or other advice on which reliance should be placed. No opinion given in the material constitutes a recommendation by EBC or the author that any particular investment, security, transaction, or investment strategy is suitable for any specific person.

Sources

1) Federal Reserve History, LTCM near failure overview

2) Federal Reserve FOMC statements

3) Bank of England working paper on the 2022 gilt market crisis