In currency crises, the most significant moments are seldom the initial sell orders. Rather, they occur when policymakers acknowledge that their defense is unsustainable. Black Wednesday marked the point at which sterling was no longer defended within Europe’s fixed-rate system and the pound was permitted to float.

This event was significant because it demonstrated the speed with which global capital can undermine a government’s exchange-rate commitment. The episode remains relevant, as similar credibility constraints continue to shape the viability of every pegged, banded, or managed currency regime.

Key facts: Black Wednesday at a glance

Date: 16 September 1992

Regime: UK membership of the Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM), with a central rate of £1 = DM 2.95 (Deutsche Mark) and a wider 6% band

Defence tools used: foreign exchange intervention and emergency interest-rate announcements (Minimum Lending Rate (MLR) raised to 12%, 15% announced then rescinded)

Outcome: sterling suspended ERM participation and moved to a floating exchange rate

The ERM Commitment and the Underlying Band Dynamics

Sterling’s Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM) entry in October 1990 embedded a simple promise: within the permitted fluctuation margins, the authorities would use intervention and interest rates to keep the exchange rate aligned with its central parity. The UK joined with £1 = DM 2.95 (Deutsche Mark) and, crucially, the wider 6% band, not the narrower margins used by several core members. That wider band was designed to buy flexibility.

At DM 2.95, the implied ERM corridor ran roughly from DM 2.773 to DM 3.127. When sterling drifted toward the floor, policy had two choices: raise the expected return on sterling assets by raising rates, or reduce supply by intervening to buy sterling with reserves. Both tools depend on credibility.

A temporary rate rise only deters selling if investors believe it will last long enough to impose real pain on shorts. Reserve intervention only deters selling if investors believe the stock of reserves and political will are large enough to outlast the market.

By mid-1992, market participants increasingly doubted the sustainability of either policy tool.

German Reunification and the Immediate Policy Mismatch Priced by Markets

The ERM’s design assumed broadly aligned inflation and business cycles. German reunification broke that assumption. Germany faced fiscal expansion and inflation risks that pushed policy toward tighter settings, while the UK was trying to escape a weak recovery and falling inflation.

The Bank of England later summarized the tension directly: German interest rates rose to meet reunification’s inflationary and fiscal consequences, while in the UK the ERM commitment constrained the scope for cutting nominal rates below Germany’s. Real rates rose as the domestic inflation outlook improved, worsening the trade-off between growth and inflation.

Markets do not need a formal forecast to detect that conflict. They infer it from yield differentials, the cost of forward cover, and the political feasibility of defending a parity. When the domestic economy is fragile, the perceived maximum tolerable interest rate becomes a ceiling on defense. Once traders believe the ceiling is below the required level, the attack becomes rational, not merely speculative.

The Build-Up: Political Catalysts and a Narrowing Confidence Window

By late summer 1992, the ERM was already strained by divergent fundamentals. Then politics tightened the timetable. The Bank of England identified the French referendum on the Maastricht Treaty, scheduled for 20 September, as an immediate focal point for market tensions. If ratification failed, investors judged a realignment more likely. This created a narrow period in which markets were incentivized to push first and ask questions later.

The pressure intensified after the lira’s devaluation and the swirl of commentary around whether ERM parities were sustainable. The Bank of England’s account notes that, after the lira’s move and comments attributed to the Bundesbank president, pressure “came to a head.” Crucially, the defense of sterling increasingly required pushing it toward levels against the US dollar that were widely seen as overvalued, undermining the credibility of the policy stance.

When a currency defense appears to disregard underlying valuation, it becomes counterproductive. Each movement toward the lower band encourages additional selling, as the anticipated gains increase if the peg fails and the currency adjusts to its fundamental values.

Black Wednesday: Transition from Defense to Floating in a Single Day

The decisive sequence on 16 September is unusually well documented in the Bank of England’s own operational narrative.

Sterling opened under intense pressure. By the early morning, it had fallen near the ERM floor, and the Bank undertook “very heavy” overt intervention, supported by other central banks. Money-market pricing quickly reflected expectations of an official response, with short-dated rates jumping as traders anticipated emergency tightening.

At 11:00 am, with sterling still at its lower ERM limit, the authorities announced MLR at 12%. Clearing banks followed with higher base rates. The signal was clear: Britain would pay for the peg with tighter financial conditions. The market’s response was clearer: it kept selling.

By early afternoon, funding stress accelerated. The Bank’s record describes one-month rates rising sharply and overnight money trading at punitive levels as settlement needs built around intervention. It was the classical mechanics of a defense: intervention drains domestic liquidity, and liquidity stress pushes short rates up, whether policymakers want it or not.

At 2:15 pm, a further escalation arrived: a 15% MLR increase was announced for the following day. Yet even this did not lift sterling off the floor. By the close of ERM operating hours, the assessment became unavoidable.

Just after 7:30 pm, the Chancellor announced the suspension of sterling’s ERM participation and rescinded the 15% decision.

By 9:30 am the next day, MLR was reduced back to 10%, confirming that the defense had run into its domestic constraint.

This was the point at which the pound “floated” in practical terms. Outside the ERM, sterling’s price was no longer bound by a policy corridor. It became a market-clearing exchange rate again.

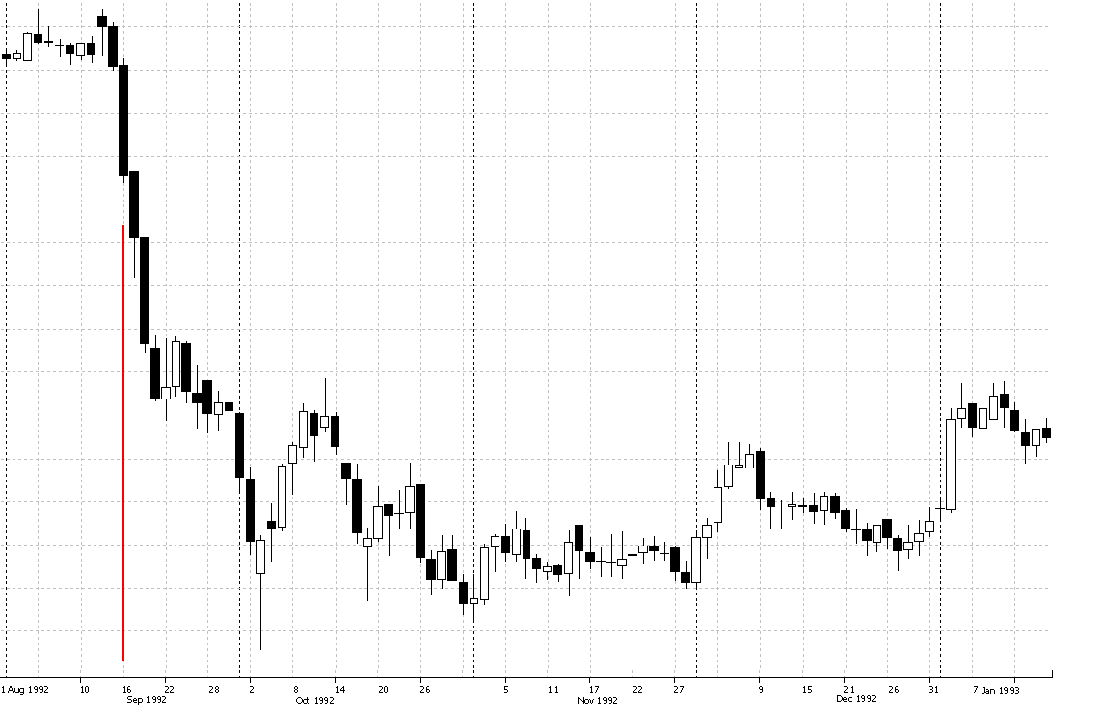

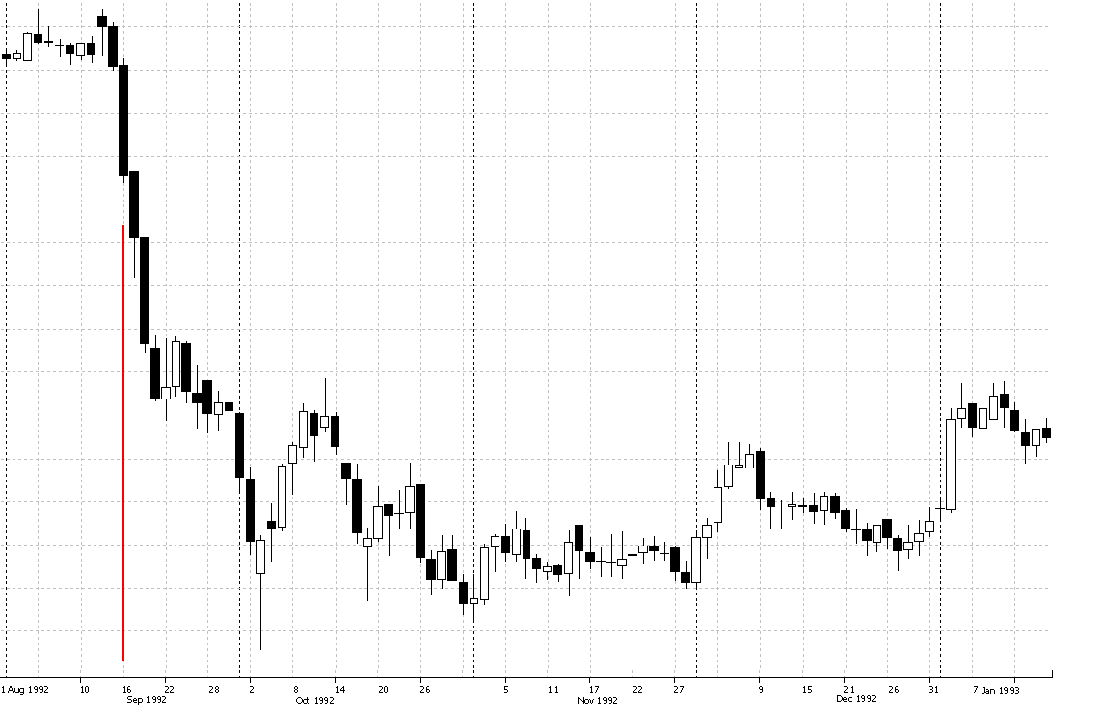

Market Repricing: Evidence from Post-Float Data

The immediate repricing is visible in the Bank of England’s selected-date table of interest rates and exchange rates. In the days around the break:

The immediate repricing is visible in the Bank of England’s selected-date table of interest rates and exchange rates. In the days around the break:

| Date (1992) |

$/£ |

DM/£ |

One-month sterling interbank (percent) |

Three-month implied future rate (percent) |

| 14 Sept |

1.8937 |

2.8131 |

10 3/32 (10.09) |

10.26 |

| 16 Sept |

1.8467 |

2.7784 |

27.00 |

11.35 |

| 18 Sept |

1.7435 |

2.6100 |

10 3/16 (10.19) |

8.40 |

| 30 Sept |

1.7770 |

2.5095 |

9 7/32 (9.22) |

8.20 |

The exchange-rate leg is the cleanest read. From 14 to 18 September, DM/£ fell from 2.8131 to 2.6100, a drop of about 7.2% , and it continued lower by month-end.

The interest-rate leg shows the regime shift even more starkly: funding stress forced extreme prints on 16 September, but by 18 September the implied future rate had collapsed, consistent with the market anticipating easier policy once the exchange-rate constraint was removed.

This is what a policy constraint looks like when it snaps. The exchange rate weakens, financial conditions ease amid expected rate cuts, and the economy receives stimulus from net exports and lower real borrowing costs.

The Deeper Lesson

It is tempting to frame Black Wednesday as a battle between the Treasury and speculators. The more durable interpretation is institutional. A fixed exchange-rate promise is a contingent contract. It only holds if markets believe the state’s reaction function is consistent with the peg under stress.

The IMF’s discussion of the 1992 ERM crisis focuses on how speculative pressure can be launched and rapidly scaled in integrated markets, and how central banks can be forced to resort to defensive measures that worsen domestic conditions.

The Bank of England’s own narrative makes the constraint explicit: a defensive rise in interest rates was unlikely to be seen as credible because it was so at odds with the domestic economy's needs. Once traders accept that logic, the equilibrium shifts. The peg becomes a one-way option for the market.

How the Pound’s Float Reshaped UK Policy Perspectives

The end of ERM membership did not end the need for a nominal anchor. It changed the anchor's form. Research on the ERM crisis notes that 1992-93 was a turning point in thinking about using the exchange rate as the central disinflation tool in open capital markets.

The UK’s experience reinforced a practical sequencing lesson: monetary credibility is more robust when it is built around a domestic target and a transparent reaction function, rather than an externally imposed parity that may conflict with the cycle.

In the short run, the post-float mix was straightforward. Sterling depreciation eased monetary conditions immediately, and the Bank was able to signal reductions later in September, complementing the easing delivered by the weaker currency. The price signal shifted from “defend the floor” to “stabilize domestic conditions,” even as fiscal discipline remained a constraint.

In the longer run, Black Wednesday became a reference point for how Britain thought about Europe, central bank credibility, and the political economy of macro adjustment. The lesson was not that floating is painless. It was that forcing an exchange-rate regime to do a job it cannot do invites a more abrupt correction later.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1) What was Black Wednesday?

Black Wednesday was 16 September 1992, when the UK suspended sterling’s membership of the European Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM) after heavy intervention and emergency interest-rate announcements failed to keep the pound above its required floor. The policy regime shifted from defending a fixed band to allowing the pound to float.

2) Why did the UK join the ERM in the first place?

The ERM was intended to stabilize exchange rates in Europe and provide a nominal anchor for disinflation. The UK joined with a central rate of £1 = DM 2.95 in the wider 6% band, aiming to import anti-inflation credibility through a stable link to core European currencies.

3) What triggered the crisis in September 1992?

The crisis was the product of a widening policy mismatch and a political catalyst. German reunification kept German rates high, while the UK economy needed easing. Market pressure intensified ahead of the French Maastricht referendum, which concentrated speculation on the probability of an ERM realignment and made sterling’s defense less credible.

4) Did interest rates really go to 15 %?

A rise in MLR to 15% was announced at 2:15 pm on 16 September, to be effective the following day, but it was rescinded when sterling’s ERM participation was suspended that evening. The next morning, the Bank confirmed that the 15% decision had been rescinded, and MLR was reduced to 10%.

5) How far did sterling fall once it floated?

The Bank of England’s selected-date series shows rapid depreciation in the immediate aftermath. DM/£ moved from 2.8131 on 14 September to 2.6100 by 18 September, and $/£ moved from 1.8937 to 1.7435 over the same window, reflecting a swift repricing once the band constraint disappeared.

Conclusion

Black Wednesday was not a mysterious event. It was the logical endpoint of a policy mismatch that markets could measure in real time. A fixed-rate commitment required the UK to carry German-style tightness through a fragile domestic cycle, and the political calendar compressed the market’s test into a single decisive week.

When sterling hit the floor, two rate escalations and heavy intervention failed because traders no longer believed the policy could be sustained.

The pound's floating was therefore less a technical adjustment than a regime reset. Exchange rates repriced quickly, funding stress spiked and then reversed, and domestic policy constraints loosened. The enduring lesson is structural: in an open capital market, credibility is the scarce resource. When a currency regime demands actions that politics and the real economy cannot support, markets will eventually force the float.

Disclaimer: This material is for general information purposes only and is not intended as (and should not be considered to be) financial, investment or other advice on which reliance should be placed. No opinion given in the material constitutes a recommendation by EBC or the author that any particular investment, security, transaction or investment strategy is suitable for any specific person.

Sources

1) https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/annrep/ar1992en.pdf