In November 2025, People's Republic of China crossed a milestone few predicted: its trade surplus in goods alone topped US $1 trillion for the first time ever. While that number alone might look like a headline statistic, its implications ripple through global manufacturing, geopolitics, and supply-chain strategies.

This is not just about a booming export sector, but also a signal that China remains a linchpin of global trade, and that the structural imbalances reshaping economies worldwide are intensifying.

In the face of persistent trade tensions, weak domestic demand at home, and shifting global market dynamics, this surplus raises fundamental questions: how sustainable is export-led growth for China? And how will the rest of the world respond to a China whose manufacturing dominance just got harder to ignore?

What the Numbers Say: The Scale of China's Trade Surplus in 2025

According to the most recent official data, during the first 11 months of 2025, China's goods trade surplus reached roughly US $1.076 trillion — marking the first time the country has crossed the $1 trillion threshold.

November alone was an exceptional month: exports rose by 5.9% year-on-year, while imports increased by only 1.9%, producing a monthly surplus of about US $112 billion, one of the largest surpluses China has ever recorded.

To put it in context: in 2024 China's trade surplus was already a record high, about US $992 billion. The 2025 figure thus represents a large leap, underscoring how export momentum has not only persisted but accelerated.

These numbers reflect a widening gap between China's exports and imports, underscoring a persistent export-driven growth model amid tepid domestic demand.

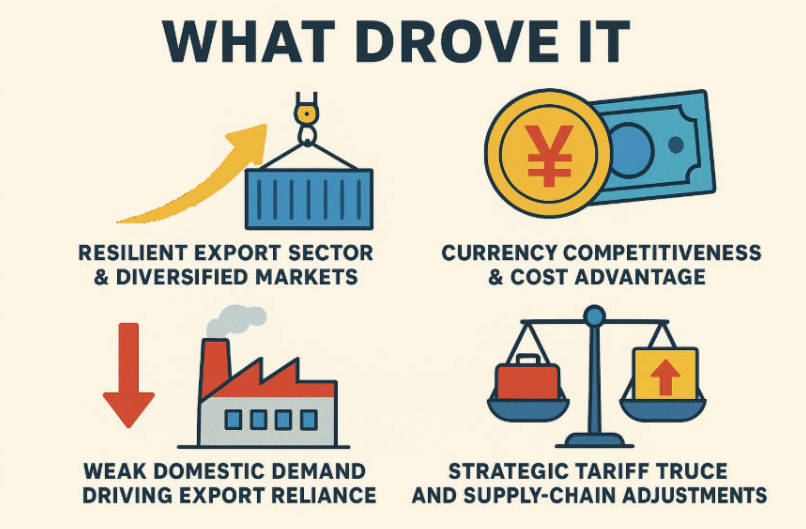

What Drove It: Key Factors Behind the Surge in China Exports

Several factors, both structural and cyclical, combined in 2025 to push China's surplus beyond $1 trillion:

1. Resilient Export Sector & Diversified Markets

Although exports to the United States of America slumped sharply, reportedly down nearly 29% in November compared with a year earlier, China managed to compensate by ramping up shipments to other regions. Markets such as the European Union and Southeast Asia saw robust demand.

This shift indicates that China is successfully re-orienting its trade flows away from traditional markets under pressure, tapping into emerging demand in markets less affected by tariffs or trade tensions.

2. Currency Competitiveness & Cost Advantage

A relatively weakened Renminbi (in global comparison) has helped make Chinese exports more price-competitive internationally. This currency effect, combined with a large industrial base and economies of scale, allowed Chinese manufacturers to undercut rivals on price, reinforcing export growth.

3. Weak Domestic Demand Driving Export Reliance

At home, China's economy continues to contend with sluggish consumer demand, a prolonged property-sector slump, and cautious consumer behaviour. These challenges have limited import demand. With fewer domestic sales opportunities, many firms turned outward, increasing export volumes to compensate.

4. Strategic Tariff Truce and Supply-Chain Adjustments

Earlier in 2025, a partial truce in tariff tensions, particularly between China and the US, helped ease some trade pressure. Conservative manufacturing firms appear to have adjusted supply chains accordingly, redirecting goods to markets with more stable or favourable trade conditions.

These factors, in combination, created a "perfect storm": strong external demand in diversified markets; cost advantages; and weak domestic consumption pushing firms to chase growth abroad.

Global Trade Imbalance Deepens: Ripple Effects Worldwide

With such a large surplus, the gap between major exporters and importers has widened — fueling a global trade imbalance with far-reaching implications:

Competitive Pressure on Manufacturing Worldwide:

Countries that traditionally produced consumer and industrial goods face competitive pressure from cheap Chinese exports. This is especially acute in sectors like electronics, machinery and mass-market goods.

Currency & Capital Flow Disruptions:

Massive inflows linked to surplus earnings can influence currency valuations and capital flows globally, affecting trade competitiveness and monetary policy in partner economies.

Strain in Trade Relations:

A sustained large surplus often leads importing countries to accuse exporters of unfair trade practices, subsidies or dumping — which can trigger protectionist measures.

In short, China's surplus isn't just a domestic achievement but also reshapes global trade dynamics and redraws the competitive landscape.

Trade Tensions Revisited: Implications for US–China Relations

The marked drop in Chinese exports to the US, nearly 29% in November compared with a year prior, underscores the continuing impact of tariffs and trade friction.

Yet, the fact that China managed to offset that kind of decline via other markets weakens some of the leverage that trade restrictions once provided. Export-led growth outside the US blunts the intended pressure.

For US policymakers and industries, that raises a critical challenge: tariffs alone may no longer be sufficient to contain Chinese export dominance. As a result, tensions could shift toward technology controls, export-licence restrictions (especially for advanced manufacturing), or broader industrial policy, rather than just tariffs on finished goods.

Beijing's Dilemma: Export-Driven Growth vs Domestic Rebalancing

China's leadership faces a paradox. On one hand, the surplus showcases the strength and resilience of manufacturing and exports. On the other, it highlights structural weaknesses: weak domestic consumption, overcapacity in manufacturing, and a lack of balanced internal demand.

Recognising this, China has signalled intent to pivot toward bolstering domestic demand. Reports indicate that 2026 may bring more proactive fiscal and monetary measures, from possible interest-rate cuts to increased government spending, aimed at stimulating household consumption and investment.

The challenge: turning export-led success into sustainable domestic growth. That requires structural reforms, improved consumer confidence, and investment in higher-value sectors — all while keeping export dynamics intact.

What It Means for the Global Supply Chain & Industry Trends

China's surplus isn't just about volume — it's shaping how global supply chains realign:

Diversification Beyond the US:

As China increases exports to Southeast Asia, the EU, Latin America and Africa, supply chains become more global and less US-centric.

Rise of High-Value Manufacturing Exports:

Growth isn't limited to low-cost goods. Demand is rising for sectors like electric vehicles (EVs), semiconductors, robotics and green tech, strengthening China's role in advanced manufacturing. This shift may enable China to capture more of the global market share in high-value industries.

Pressure on Regional Producers:

Producers in Europe, Southeast Asia, and elsewhere may struggle to compete, forcing either unit cost reduction, quality upgrades, or repositioning toward niche, high-value goods.

For global manufacturing, this could accelerate a transition from low-cost, high-volume models to more diversified, high-tech, value-added supply chains, and China appears poised to lead that transformation.

Risks and Future Challenges for China's Surplus Strategy

Even as China basks in the glow of a record surplus, several risks loom:

Backlash from Trade Partners: Key trading blocs, especially the EU, are already raising concerns. Some leaders warn of potential retaliatory tariffs if China's surplus and export dominance persist.

Global Demand Fluctuations: A slowdown in global demand, perhaps due to recessionary pressures, inflation, or regional instability, could sharply dent export growth and erode the surplus.

Domestic Overreliance on Exports: Continuing to depend heavily on exports masks China's domestic structural issues. Without stronger domestic demand, economic growth could be vulnerable to external shocks.

Supply-Chain and Geopolitical Risk: As countries diversify supply chains, impose stricter regulations, or boost local manufacturing, China's advantage might erode over time.

Long-term sustainability of a huge surplus is uncertain, especially if global trade dynamics shift or external demand softens.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Why has China's trade surplus exceeded $1 trillion in 2025?

Because exports soared, aided by diversified markets in Europe and Southeast Asia, competitive currency levels, and weak domestic demand at home, while imports rose only modestly. That combination widened the goods-trade gap significantly.

Q2:Does this surplus include services trade or only goods?

The reported surplus is for goods only. Services trade (imports and exports of services) is subject to different dynamics and is not included in the $1 trillion figure.

Q3: How did exports to the US perform in 2025?

Exports to the US fell significantly, by nearly 29% in November year-on-year, as tariffs and trade friction continued. However, China offset that decline by boosting exports to other regions like the EU and Southeast Asia.

Q4: Can China maintain this trade surplus long-term?

Sustaining such a high surplus will be difficult. Risks include global demand slowdown, regulatory backlash abroad, overreliance on exports, and China's own need to rebalance toward domestic demand. Structural reforms will be required.

Q5: What does this mean for global supply chains?

The surplus underscores China's strengthening role in global manufacturing and exports, accelerating supply-chain diversification toward China-centric manufacturing. This may pressure regional producers and reshape industrial competition globally.

Conclusion

China's crossing of the $1 trillion trade surplus mark is more than a milestone: it's a statement. It confirms that China remains the world's manufacturing powerhouse and that its influence on global trade dynamics is growing stronger.

But this record is not an endpoint but a crossroads. The real question now isn't just how China exports, but whether it can rebalance: build consumer confidence at home, invest in high-value industries, and transition from export-driven growth to a more diversified, resilient economy.

Meanwhile, the global community must decide how to respond: with protectionist backlash, strategic supply-chain realignment, or cooperation and regulation. The next few years will shape not just China's economic trajectory, but the architecture of global trade itself.

Disclaimer: This material is for general information purposes only and is not intended as (and should not be considered to be) financial, investment or other advice on which reliance should be placed. No opinion given in the material constitutes a recommendation by EBC or the author that any particular investment, security, transaction or investment strategy is suitable for any specific person.