A derivative is a financial contract whose value comes from something else - such as a currency pair, index, interest rate, commodity, or stock. You are not trading the asset directly; you are trading an agreement tied to its price.

For traders, derivatives matter because they allow exposure with smaller capital, enable hedging, and offer ways to profit in rising or falling markets. They also increase both opportunity and risk..

Definition

In trading terms, a derivative is a contract whose price changes based on movements in an underlying instrument such as EUR/USD, gold, oil, or an index. Common derivatives include futures, options, forwards, and CFDs.

Traders use them for speculation, hedging, and managing exposure. Because many derivatives involve leverage, small price moves in the underlying can create large gains or losses in a derivative position.

Traders see derivatives on their platforms as CFDs, options chains, futures contracts, or swap rates. CFD traders watch margin, leverage, and spread. Futures traders monitor contract expiry and rollover. Options traders study volatility and strike pricing.

Professionals, funds, and institutional desks rely heavily on derivatives to manage risk, while retail traders mostly interact with CFDs and sometimes options.

Think of a concert ticket that is sold out. You do not hold the ticket yet, but you sign an agreement with a friend: if the price of the real ticket goes up, they will sell it to you at today’s price. If the price drops, you can walk away.

This contract is not the ticket itself, but its value depends on the real ticket’s market price.

Derivatives work much the same way. They are agreements whose worth mirrors the price of something else, letting you benefit from price moves without actually holding the underlying item.

What Changes Derivatives Day To Day: Forces Behind Contract Value

A derivative exists because its value depends on something else. That “something else” is called the underlying asset.

The underlying can be a currency pair, stock index, bond yield, interest rate, metal or commodity. When the underlying moves, the derivative price responds. This link is the reason the contract exists.

Several forces shape a derivative’s price:

Underlying market movement: When the underlying asset rises or falls, the derivative typically moves in the same direction.

Volatility: When markets become more uncertain, options become more expensive and CFD spreads can widen.

Interest rates and funding: Changes in overnight financing rates alter CFD costs, futures pricing, and swap values.

Time decay: Options lose value as expiry gets closer, even if the underlying price stays still.

Types Of Derivative

| Type |

What It Is |

Key Feature |

Common Use |

| Futures |

Contract to buy or sell later at a fixed price. |

Trades on an exchange with standard rules. |

Trading commodities, indices, currencies. |

| Options |

Right, not obligation, to buy or sell at a set price. |

Time decay affects value. |

Managing risk, directional or volatility trades. |

| Forwards |

Private agreement for a future trade at a set price. |

Custom terms, not exchange traded. |

Currency and commodity hedging. |

| Swaps |

Exchange of cash flows between two parties. |

Often tied to interest rates or currencies. |

Managing rate or currency exposure. |

| CFDs |

Cash-settled contract tracking price changes. |

No ownership of the asset. |

Short-term trading on indices, metals, FX. |

Why Derivatives Matter to Traders

Derivatives play a central role in global markets by offering flexibility, leverage, and risk-transfer mechanisms. They enable traders to:

Protect portfolios from price swings.

Express directional views with limited capital.

Access markets or exposures that might otherwise be unavailable.

Trade volatility, interest rates, or cross-asset relationships more precisely.

In modern markets, derivatives also support liquidity and price discovery, influencing everything from commodity pricing to corporate financing decisions.

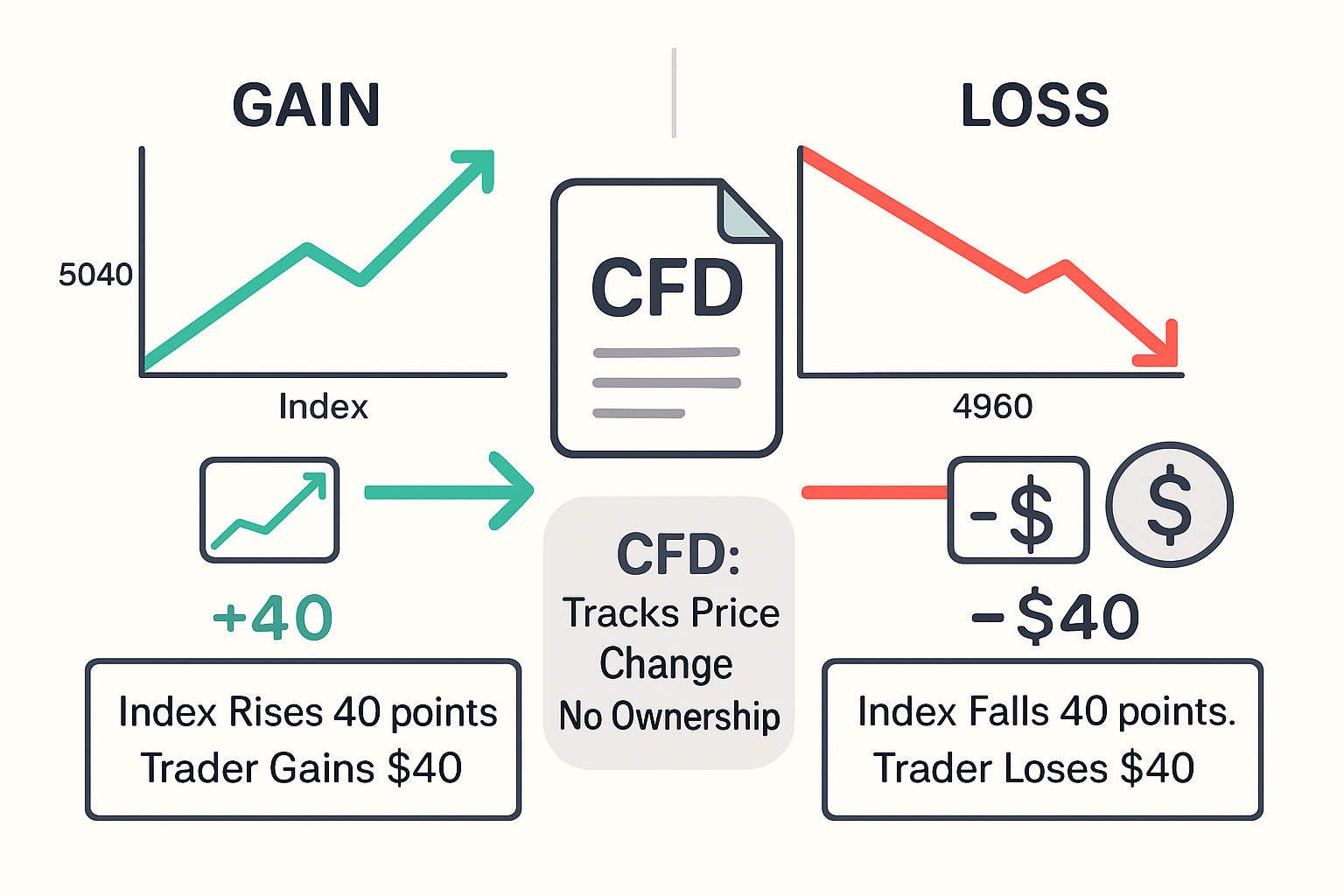

Quick Example

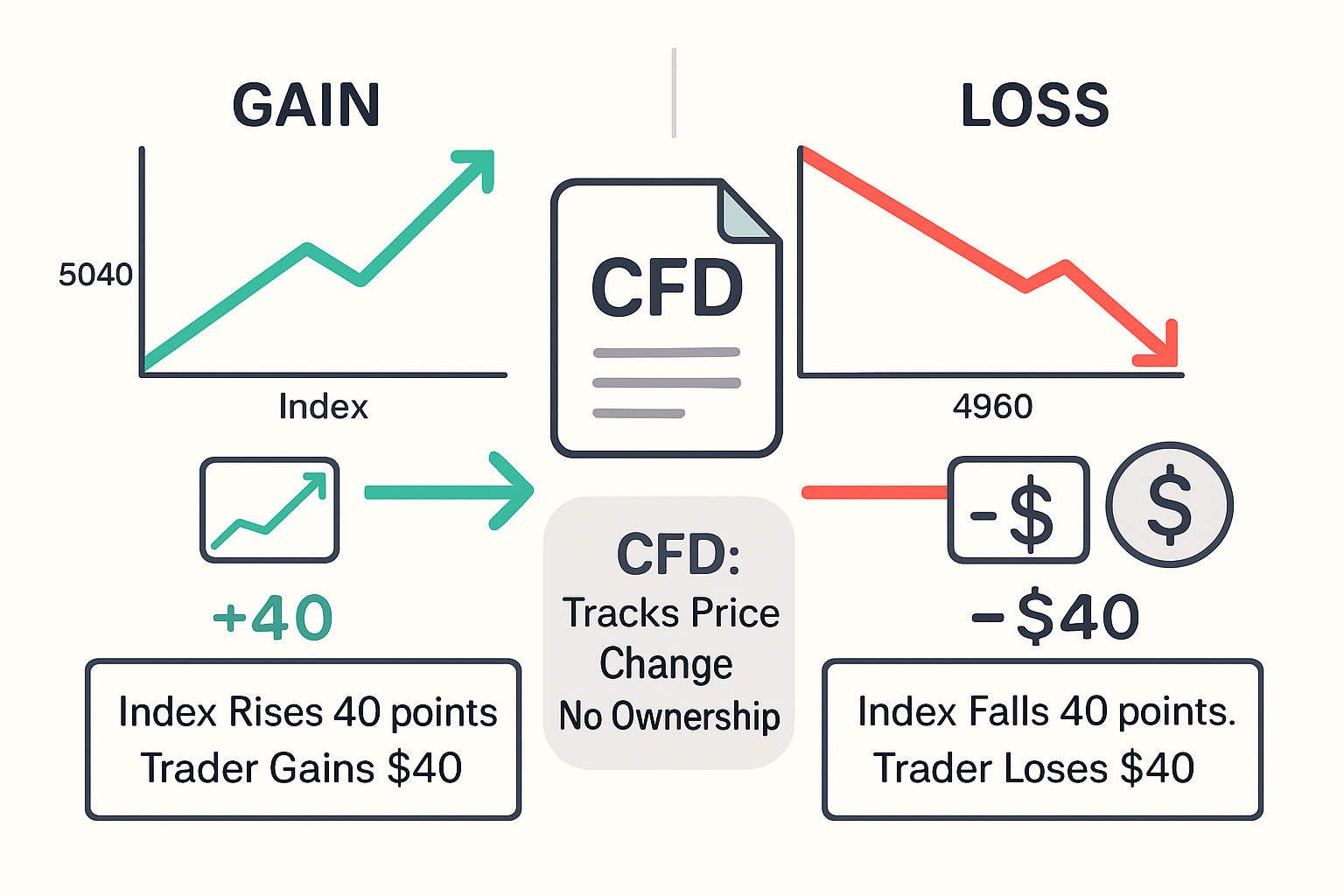

Imagine a trader buys a CFD that follows the price of an index trading at 5,000 points. The trader opens a small position worth 1 dollar per point. If the index rises to 5,040, the CFD gains 40 dollars. The trader never owns the index. The contract only tracks the change.

If the index falls to 4,960, the trader loses 40 dollars. The move is the same size, only in the opposite direction.

The contract responds point for point to the underlying index. This shows how derivatives deliver exposure without ownership. It also shows how gains and losses can grow quickly even with small price changes.

Common Mistakes That Often Hurt Beginners

Using excessive leverage: small adverse moves turn into large losses.

Ignoring funding costs: holding CFD positions long term becomes expensive.

Trading near expiry without understanding rollover: futures and options can shift unexpectedly.

Confusing volatility effects: options can lose value even when direction is correct.

Overtrading because of low margin requirements: leads to fast, uncontrolled drawdowns.

How to Check Derivatives Before You Click Buy or Sell

1. Identify the underlying asset.

Confirm what drives the derivative’s value. Review current trends, recent news, volatility levels and typical daily trading ranges to understand potential price behaviour.

2. Understand the contract type.

CFDs, futures and options each respond differently to time, settlement rules and market conditions. Know whether the contract is cash-settled or physically settled and how time decay or rollover mechanics may influence price.

3. Evaluate the spread and liquidity.

A wide spread can signal uncertainty or heightened risk, while low liquidity increases the chance of slippage. Check depth of market if available to gauge how easily positions can be opened or closed.

4. Check expiration details.

Futures and options have defined expiry dates that affect pricing as they approach settlement. Be aware of rollover costs, adjustments or changes in liquidity near expiry.

5. Review financing costs.

Holding leveraged contracts overnight often incurs financing charges. Over time these costs influence net profitability, especially in slow-moving markets.

Work through these checks before every trade. In fast-moving markets or when major news is expected, revisit them to ensure your assumptions still hold.

Related Terms

Underlying Asset: The financial instrument on which the derivative’s value is based.

Leverage: Using borrowed or synthetic exposure to control a larger position.

Hedging: Reducing risk by taking offsetting positions.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. Are derivatives only for advanced traders?

Not necessarily. Many retail traders use simple derivatives like CFDs because they offer flexible position sizing. However, derivatives require strict risk control, since leverage magnifies mistakes.

2. Do derivatives always move the same as the underlying asset?

They usually move in the same direction, but not always at the same speed. Leverage, funding charges, volatility, and time decay can make a derivative behave slightly differently from the underlying, especially during fast markets or near contract expiry.

3. Are derivatives riskier than spot trading?

They can be, mainly because leverage makes both profits and losses larger. Spot markets move at normal speed. Derivatives move faster, so they need tighter planning, defined exits, and an understanding of extra costs like funding and spreads.

4. What is the best derivative for beginners?

Many traders start with CFDs because they are simple: price in, price out, no expiry. Options and futures give more flexibility but require deeper knowledge of volatility, time decay, and margin structure. Beginners should focus on low leverage and small position sizes.

Summary

A derivative is a contract whose value depends entirely on an underlying asset, making it one of the most versatile instruments in modern trading. Whether used for hedging, speculation, or enhancing portfolio efficiency, derivatives shape liquidity and risk management across global markets.

Understanding their structure, benefits, and risks enables traders to apply them strategically and responsibly.

Disclaimer: This material is for general information purposes only and is not intended as (and should not be considered to be) financial, investment or other advice on which reliance should be placed. No opinion given in the material constitutes a recommendation by EBC or the author that any particular investment, security, transaction or investment strategy is suitable for any specific person.