Leading indicators in the stock market are tools that provide early signals of potential market direction. While they cannot predict outcomes with certainty, they offer valuable foresight when used with care.

This article breaks down the main categories of leading indicators—economic, technical, and sentiment—explains how to apply them in practice, highlights their limitations, and answers common questions investors often ask.

Key Takeaways

Early signals, not guarantees – leading indicators suggest potential market shifts but often generate false alarms.

Three main types – economic data, technical measures, and sentiment indicators each provide different forward-looking insights.

Best used in combination – no single indicator is reliable on its own; blending them increases effectiveness.

Confirmation and risk control matter – always seek price confirmation and apply stop losses or position sizing to manage risk.

Improves decision-making – when used carefully, leading indicators enhance timing and portfolio strategy without replacing judgment.

Categories of Leading Indicators

1. Economic and Macro Leading Indicators

Economic conditions shape the stock market, and several leading indicators from the wider economy provide useful foresight.

1) Yield curve / term spread:

The difference between long-term and short-term government bond yields has a strong historical track record. An inverted yield curve has often preceded recessions and market downturns.

Surveys of business managers on new orders and production activity tend to lead broader economic growth, offering clues about corporate earnings prospects.

3) Consumer confidence surveys:

Shifts in household sentiment provide signals about future spending patterns, which are critical for stock performance in consumer-driven economies.

4) Initial unemployment claims:

Rising jobless claims are often one of the first signs of an economic slowdown.

5) Composite Leading Indexes:

Organisations such as The Conference Board compile composite indexes combining multiple economic signals to provide a single measure of forward-looking momentum.

2. Technical and Market-Based Leading Indicators

Many investors look to the market itself for leading signals. Technical analysis relies on patterns and mathematical indicators derived from price and volume.

1) Momentum oscillators such as the Relative Strength Index (RSI) or Stochastic Oscillator attempt to identify overbought or oversold conditions before reversals occur.

2) Divergence signals occur when the direction of an indicator differs from price trends. For example, if prices rise but momentum weakens, it may signal a potential reversal.

3) Volume-based tools, including On-Balance Volume (OBV) or the Accumulation/Distribution index, track the strength of buying and selling pressure. Volume often leads price as informed investors build or reduce positions.

4) Volatility and breadth indicators, such as the advance/decline line or TRIN, help assess the overall health of a rally or sell-off.

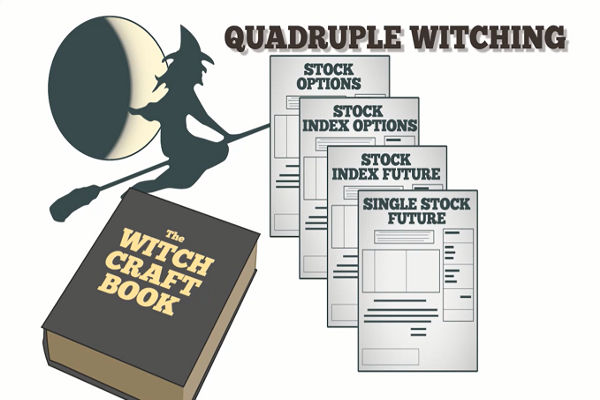

5) Cyclical or seasonal patterns, like the January Barometer or Coppock Curve, are less precise but still used by some traders as forward-looking signals.

3. Sentiment and Composite Indicators

Investor sentiment often shifts before fundamentals do, and measuring this mood can provide an edge.

1) Sentiment indexes, including "fear and greed" measures, assess whether investors are excessively bullish or bearish. Extreme readings may foreshadow turning points.

2) Media and attention indicators, such as news coverage frequency or search trends, provide insight into whether hype or panic is influencing markets.

3) Composite factor models combine elements of valuation, momentum, volatility, and sentiment into multi-signal frameworks designed to reduce reliance on any single indicator.

Using Leading Indicators in Practice

Relying on leading indicators requires discipline. Some best practices include:

1) Selecting appropriate indicators:

Traders in fast-moving markets may prefer momentum oscillators, while long-term investors may rely more on economic surveys and composite indexes.

2) Combining signals:

No single indicator is sufficient. A blend of economic, technical, and sentiment indicators often provides a more balanced picture.

3) Seeking confirmation:

Leading indicators are best used as alerts rather than guarantees. Waiting for price confirmation can help avoid false signals.

4) Testing strategies:

Historical backtesting helps evaluate whether an indicator has worked under similar conditions.

5) Managing risk:

Stop losses, position sizing, and diversification remain essential when following early signals.

Evidence and Critiques

Academic studies and practical experience show that leading indicators can improve market timing, but they are far from perfect.

For example, the yield curve has accurately predicted several recessions, but there have also been false alarms. Similarly, momentum indicators may call reversals that never materialise.

The challenge is the trade-off between being early and being accurate. Indicators that give timely warnings often produce more false positives, while those that are more reliable tend to lag behind.

Additionally, changing market structures, including the rise of algorithmic trading, can reduce the predictive power of traditional indicators.

Case Study: Using Leading Indicators in Practice

Consider a scenario in which the yield curve inverts while the PMI drops below 50. signalling contraction.

At the same time, equity market breadth weakens, with fewer stocks participating in rallies. An investor using these leading indicators may reduce equity exposure, increase defensive holdings, or raise cash reserves.

In hindsight, not all such signals result in a downturn, but when they align, they provide a valuable framework for adjusting risk before markets turn.

Limitations and Caveats

While leading indicators can be powerful, investors must treat them with caution:

They are probabilistic, not certain.

Market regimes change, reducing historical reliability.

Indicators can produce whipsaws—false starts that reverse quickly.

The timing gap between a signal and a market move can be wide, making it difficult to act effectively.

Overreliance on any single indicator increases risk.

Conclusion

Leading indicators offer investors and traders a valuable toolkit for anticipating market changes. By examining economic surveys, technical measures, and sentiment data, they provide a forward-looking perspective that lagging indicators cannot.

However, they should never be used in isolation. The most effective approach combines different types of indicators, confirms signals with price action, and applies rigorous risk management. In this way, leading indicators can enhance decision-making without creating overconfidence.

Leading Indicators in the Stock Market

| Category |

Examples |

Main Use |

Key Limitation |

| Economic |

Yield curve, PMI, confidence data |

Signal growth or slowdown |

False or early warnings |

| Technical |

RSI, OBV, advance/decline line |

Flag momentum and breadth |

Prone to market noise |

| Sentiment |

Fear/Greed Index, surveys, media |

Reveal investor psychology |

Highly volatile signals |

| Composite |

LEI, factor models |

Blend of multiple signals |

Complexity, less clarity |

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1. Can one rely solely on leading indicators to time the market?

Not reliably. Leading indicators are designed to signal ahead of trends, but they often give false positives. They should be used with confirmations and risk controls.

Q2. How many leading indicators should I use at once?

It is best to use a diversified set rather than a large number. Covering economic, technical, and sentiment dimensions ensures breadth without excessive overlap.

Q3. Over what timeframe do leading indicators tend to be more effective?

Most leading indicators are more useful over weeks to months. Macro indicators may give signals six months ahead, while technical oscillators are more short-term.

Q4. How do I deal with false signals from leading indicators?

Investors typically handle false signals by setting stop losses, waiting for confirmation, and reducing position sizes when signals are weak.

Disclaimer: This material is for general information purposes only and is not intended as (and should not be considered to be) financial, investment or other advice on which reliance should be placed. No opinion given in the material constitutes a recommendation by EBC or the author that any particular investment, security, transaction or investment strategy is suitable for any specific person.