Devaluation is when a government or central bank officially lowers the value of its currency against another currency or a basket of currencies. It happens in fixed or tightly managed exchange rate systems, where the authorities, not the market, set the rate.

In simple terms, after a devaluation you need more units of the local currency to buy the same amount of foreign currency.

This matters for traders because devaluations often arrive in sudden steps, not smooth moves. They can create sharp gaps, big changes in trends, and unusual risk in forex and related markets.

Definition

In trading, devaluation is an official policy action where a fixed or tightly managed currency is reset lower against another currency or a basket.

This is different from normal market weakness. Market weakness is a natural fall driven by supply and demand.

Devaluation is a deliberate decision. Traders usually see it when a central bank issues a formal statement or changes the band within which a currency can trade.

On trading platforms, devaluation shows up as a sudden jump in the exchange rate. If a currency is devalued by ten percent, its pair against the US dollar may immediately gap higher.

Analysts, macro traders and anyone holding positions linked to that currency watch these announcements closely. News wires, government press releases and economic calendars often highlight when such decisions may occur.

Impact Of Devaluation On Traders

A devaluation instantly shifts the relative value of assets denominated in the affected currency. For example, if a government reduces its currency’s value by 10 percent overnight, all foreign exchange pairs involving that currency reprice accordingly.

Traders may see accelerated volatility in:

FX markets, where spreads widen and liquidity may thin during the announcement.

Commodity markets, because commodity pricing often uses major reserve currencies.

Bond markets, since devaluation can raise inflation expectations and influence interest rates.

Equity markets, particularly in export-heavy economies that may benefit from a weaker currency.

Understanding the motivation and macroeconomic backdrop behind a devaluation helps traders anticipate how long these effects may persist and whether the policy signals broader economic stress.

What Changes Devaluation Day to Day

Why Some Economies Move the Peg or Fixed Rate

Several forces push a government or central bank toward devaluation.

Low foreign currency reserves.

When a country runs out of dollars or euros to defend its fixed exchange rate, it may lower the peg. When reserves fall, the currency tends to face more pressure, and devaluation becomes more likely.

Weak exports and slow growth.

If the economy struggles to sell goods abroad, a cheaper currency can make exports more attractive. When export numbers fall, the pressure to devalue can rise.

High inflation at home.

When local prices rise too fast, the currency becomes overvalued. Authorities may cut its value so it better reflects real conditions. When inflation spikes, devaluation is often used to restore competitiveness, although it can also worsen price pressures later.

These forces create signals that traders follow. When they see reserves decline, inflation jump or export numbers weaken, they start pricing the chance of a devaluation.

Quick Example

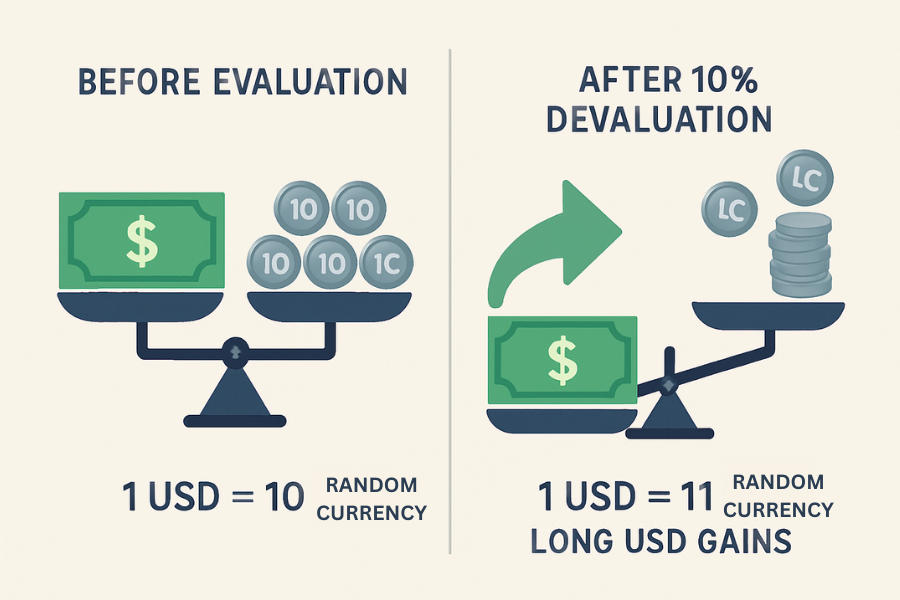

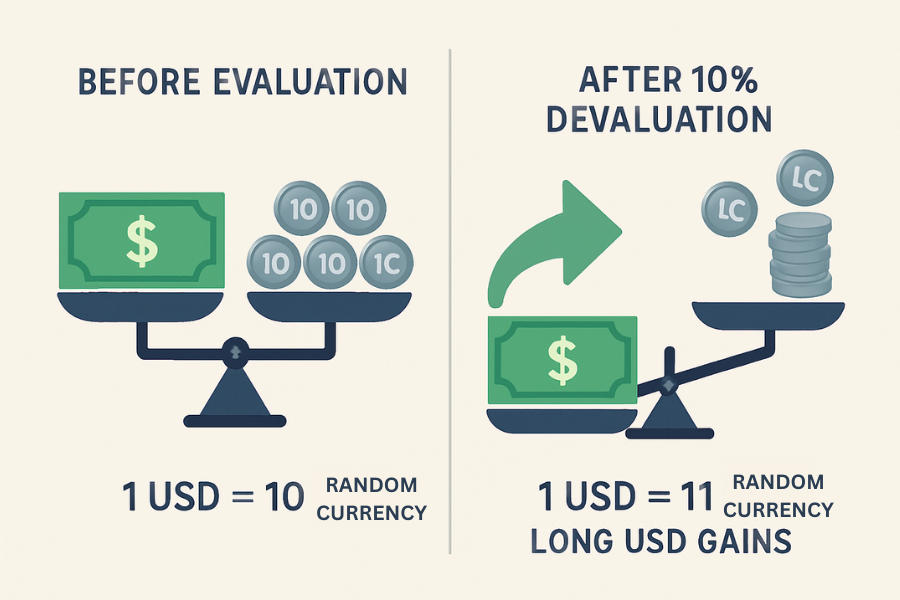

Picture a trader watching a pair where 1 dollar equals 10 units of a local currency. The trader holds a small buy position. Overnight, the government announces a ten percent devaluation. The new rate is 1 dollar equals 11 units.

The pair jumps. If the trader was long USD against the local currency, the position gains because the dollar now buys more of the currency. A move from 10 to 11 is a ten percent rise.

A small position valued at 1,000 dollars could gain 100 dollars on paper.

If the trader was short the same pair, the outcome flips. The position faces a loss because the local currency now has lower value. The trader may face a stop out if they did not size the trade correctly.

This shows how a quick policy change can alter results even without normal market trading.

How to Check Devaluation Risk Before You Trade

Key Signals to Watch on Your Platform and in the Market

Check the currency regime.

If the country has a fixed or managed rate, devaluation is possible. Free floating currencies do not have official devaluations.

Watch central bank press releases.

Sudden statements outside normal meeting dates may signal stress.

Look at spreads

If spreads widen at quiet times, it may signal lower confidence.

Check reserve data.

When foreign reserves drop for several months, risk builds.

Follow inflation reports.

If inflation far exceeds the target, the currency may be under pressure.

Check these items at least once a day when trading a pair linked to a managed currency. Before any major economic release, review them again.

Related Terms

Depreciation: A natural decline in a currency’s value due to market forces rather than policy actions.

Revaluation: The official increase in the value of a currency under a fixed or managed exchange rate system.

Monetary Policy: The set of tools used by a central authority to manage economic conditions, including interest rates and money supply.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. What is the main difference between devaluation and depreciation?

Devaluation is a policy move made by authorities. Depreciation is a natural fall caused by market forces. Only fixed or managed currencies can be devalued.

2. Does devaluation always boost exports?

A cheaper currency can help exports, but the effect depends on demand, supply chains and how quickly companies adjust prices. High inflation can limit the benefit.

3. Can traders predict a devaluation?

No one can know for sure. Traders watch reserves, inflation, trade data and government comments to judge risk. These signals help prepare but do not guarantee timing.

4. How does devaluation affect inflation?

Imported goods become more expensive. This can push inflation higher. Authorities must balance export benefits with the risk of rising prices.

Summary

Devaluation is the intentional reduction of a currency’s value by a governing authority. It is a strategic tool often used to address trade imbalances or competitiveness concerns, but it comes with significant risks including inflation, capital flight, and investor uncertainty.

For traders, a devaluation can rapidly shift price dynamics across foreign exchange, bond, commodity, and equity markets.

Understanding why a devaluation occurs and how it interacts with broader economic fundamentals allows traders to respond with clarity and well-reasoned strategy.

Disclaimer: This material is for general information purposes only and is not intended as (and should not be considered to be) financial, investment or other advice on which reliance should be placed. No opinion given in the material constitutes a recommendation by EBC or the author that any particular investment, security, transaction or investment strategy is suitable for any specific person.