Welles Wilder's Forgotten Masterwork

J. Welles Wilder Jr. stands among the most influential figures in the history of technical analysis. His name is permanently etched into trading systems through widely used indicators such as the Relative Strength Index (RSI), Average True Range (ATR), Directional Movement Index (ADX), and Parabolic SAR. These tools have shaped generations of traders and analysts.

Yet, one of his least-discussed contributions — The Adam Theory of Markets or What Matters is Profit (1987) — offers a more philosophical and conceptual perspective on markets.

Unlike his mechanical indicators, this theory dives deep into how humans perceive market movements, aiming to uncover a universal model behind price action and trader psychology.

This article explores the essence of Wilder's Adam Theory, explaining its logic, visual methods, and enduring relevance to modern trading.

The Genesis of the Adam Theory

In the early 1980s, financial markets were shifting. The dominance of mechanical trading systems was giving way to behavioural interpretations of price movements. Against this backdrop, Wilder sought to develop a framework that unified human perception and market geometry.

At the heart of his exploration lay the metaphor of "Adam", representing an unbiased, pure observer of market behaviour.

The idea was simple yet profound: if one could observe the market as "Adam" — free from emotional and cognitive bias — patterns of symmetry and reflection would emerge naturally.

Wilder's motivation stemmed from a deep belief that markets were not random but structured reflections of collective human behaviour. The Adam Theory was his attempt to map that structure visually and logically.

The Core Idea: Market Symmetry and Human Perception

At its foundation, The Adam Theory of Markets or What Matters is Profit rests on the concept of market symmetry. Wilder proposed that markets tend to move in mirrored patterns around significant turning points — a notion he called the Reflection Principle.

Key components of this idea include:

Symmetrical Movement: After a clear turning point, price action often replicates its past movement, mirrored across that pivot.

Human Bias: Traders' emotions — fear, greed, and hope — distort perception, leading to missed opportunities.

Behavioural Geometry: By combining geometry and psychology, Wilder aimed to offer traders a way to visualise both structure and sentiment.

This theory suggests that understanding symmetry is not about predicting the future but recognising balance and imbalance within the ongoing rhythm of price movements.

Key Concepts of Market Symmetry in The Adam Theory of Markets or What Matters is Profit

| Concept |

Description |

Practical Implication |

| Symmetry |

Market moves reflect previous waves |

Identify potential reversal zones |

| Reflection Principle |

Price mirrors its pattern after a pivot |

Helps in pattern projection |

| Perception Bias |

Emotional distortion affects analysis |

Cultivate objectivity like "Adam" |

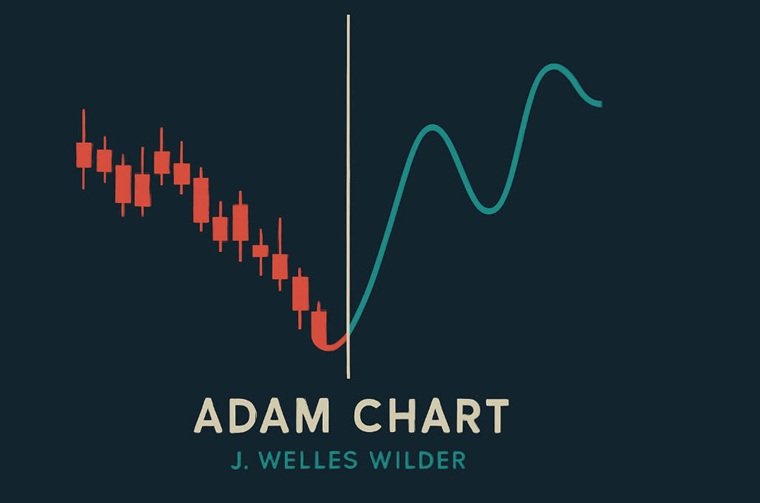

The Adam Chart: Visualising Market Symmetry

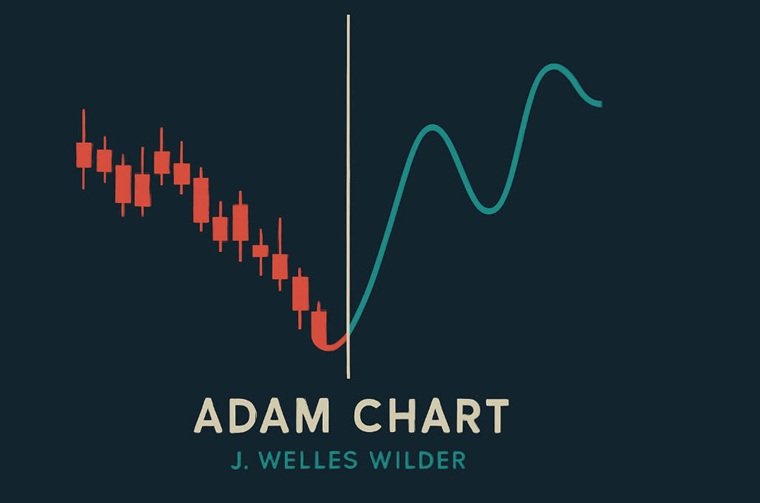

The Adam Chart is the visual foundation of Wilder's theory. It is a tool for recognising and projecting symmetrical price behaviour.

Construction Steps:

Identify a major turning point (swing high or low).

Draw a vertical axis through that pivot — the line of symmetry.

Reflect the preceding price structure across this line to project the potential future path.

Compare the mirrored pattern with actual price movement for confirmation.

Wilder argued that the market often respects these reflections because collective trader psychology tends to react similarly after a reversal.

When compared to tools like Fibonacci retracements or Gann angles, the Adam Chart is less mathematical and more visual and conceptual. It relies on observation and discipline rather than formulaic precision.

Comparing the Adam Chart with Other Symmetry-Based Analytical Tools

| Method |

Basis |

Similarity to Adam Theory |

Difference |

| Fibonacci Retracements |

Ratio-based |

Both identify turning zones |

Fibonacci is numeric; Adam is visual |

| Gann Angles |

Geometric angles |

Both use geometry |

Gann uses time-price relations |

| Adam Chart |

Reflective symmetry |

Visual and intuitive |

Lacks numerical fixedness |

What Matters is Profit: Wilder's Pragmatic Philosophy

The subtitle of the book — What Matters is Profit — encapsulates Wilder's practical philosophy. He recognised that theoretical perfection was less important than consistent, disciplined execution.

Wilder believed that:

Profitability outweighs complexity: Traders should prioritise results, not elegant theories.

Discipline and flexibility are vital: Adapt strategies when evidence changes.

Objectivity is strength: Success depends on eliminating emotional interference.

The Adam Theory reinforces this pragmatism by encouraging traders to observe rather than anticipate, aligning with the principle that "the market is never wrong, only our interpretation is."

Integrating the Adam Theory into Modern Trading

Although conceived in the 1980s, the Adam Theory has surprising relevance in the age of algorithmic and AI-driven trading. Its concept of symmetry aligns closely with how modern quantitative systems detect fractal and reflective patterns.

Practical integration ideas:

Pattern Projection: Use symmetry to model potential reversal zones.

AI Training Data: Incorporate reflection principles into pattern-recognition algorithms.

Indicator Confirmation: Combine with Wilder's RSI or ADX for multi-layer validation.

Discretionary Trading: Apply Adam symmetry to visual chart analysis, especially during volatile swings.

For example, in a strong uptrend, identifying a mirrored structure around a key high may help anticipate retracement zones — not as a prediction, but as a contextual guide for managing trades.

Criticism and Limitations

Despite its depth, The Adam Theory of Markets or What Matters is Profit did not achieve the same popularity as Wilder's other works.

Main criticisms include:

Subjectivity: The mirrored patterns are open to interpretation, leading to inconsistent results.

Overfitting Risk: Traders may see symmetry where none truly exists.

Conceptual Ambiguity: The lack of strict mathematical definition makes automation difficult.

However, many modern theorists have revisited the concept through pattern-recognition algorithms, seeking to translate Wilder's qualitative insights into quantitative frameworks.

Legacy and Continuing Relevance

Beyond charts and symmetry, Wilder's greatest legacy in the Adam Theory lies in its philosophical perspective. He invited traders to view markets as reflections of human behaviour rather than mechanical entities.

"Adam" symbolises the objective observer, someone who sees price action without the filters of emotion or bias. In this way, the theory becomes a meditation on perception and awareness, not just a method of analysis.

Its enduring lesson is that recognising symmetry is less about forecasting and more about understanding — seeing the market for what it is, not what we hope it to be.

Conclusion: Reclaiming Wilder's Vision

The Adam Theory of Markets or What Matters is Profit represents Welles Wilder's bridge between intuition and structure. It challenges traders to balance technical precision with perceptual clarity.

In reclaiming Wilder's vision, we are reminded that every trading method — however elegant — must ultimately serve a single purpose: to achieve consistent, rational profit. Yet, as Wilder taught, profit without perception is hollow.

In the end, both the market and the trader mirror each other — and the clearer the reflection, the closer we come to understanding what truly matters.

Disclaimer: This material is for general information purposes only and is not intended as (and should not be considered to be) financial, investment or other advice on which reliance should be placed. No opinion given in the material constitutes a recommendation by EBC or the author that any particular investment, security, transaction or investment strategy is suitable for any specific person.