When you trade or invest, you are not only reacting to the headline profit number. You are trying to understand how strong the core business is, and whether that strength is improving or fading.

The problem is that reported earnings can look better or worse because of debt costs, tax timing, and accounting charges, even when the underlying operations did not change much.

That is why analysts often use a metric called EBITDA that focuses on operating performance in a more comparable way across companies and industries. In this article, you will learn how to read it properly, how it is used in valuation and credit analysis, and the key limitations that can cause traders to misjudge a company’s real earning power.

What Is EBITDA?

EBITDA stands for Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation, and Amortization. It is a measure designed to approximate operating profitability by excluding interest and taxes, and adding back depreciation and amortization.

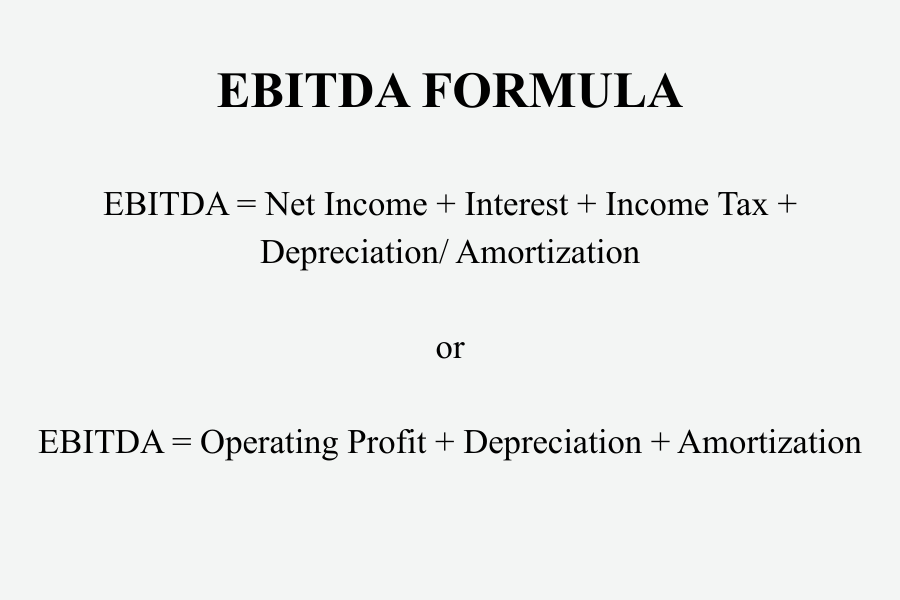

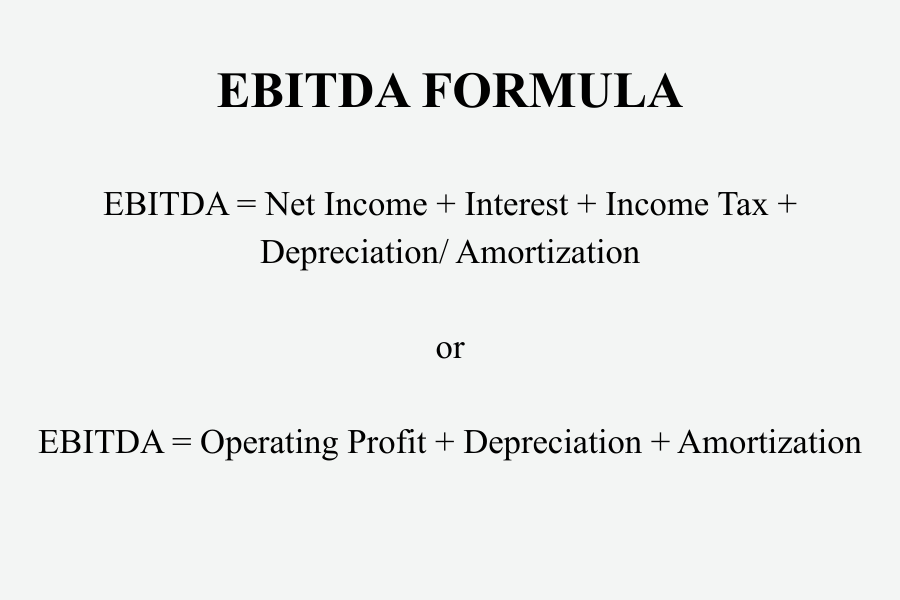

You can calculate EBITDA starting from net income by adding back interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization. Some analysts start from operating income (EBIT) and then add depreciation and amortization, which often gets you close, but the cleanest approach is to follow the company’s own reconciliation and check what they included.

EBITDA is widely used in ratios like EV to EBITDA and in leverage metrics like net debt to EBITDA, so it shows up a lot in equity research and loan documents. It works best as a comparison tool within the same industry, but you still have to check the details, especially when companies report “adjusted EBITDA” that removes extra costs to make results look smoother.

Why EBITDA Is Used

Net profit reflects the final earnings available to shareholders after all expenses. While comprehensive, net profit can distort comparisons between businesses due to differences in leverage, tax jurisdictions, and accounting policies.

EBITDA addresses this limitation by focusing on operational earnings power. It allows investors to assess how effectively a company generates income from its business model before financial and accounting decisions are applied.

EBITDA is commonly used in:

How to Calculate EBITDA

EBITDA is not always reported directly in financial statements. Investors often need to calculate it using information from the income statement.

Common EBITDA Formulas

From Net Income:

From Operating Profit:

Both approaches yield the same result when the inputs are accurate.

Quick Example

Imagine a company earns $1,000,000 in revenue in a year. Its operating costs, such as wages and materials, total $700,000. That leaves $300,000. This is the base for EBITDA.

Now add other costs. Interest on loans is $50,000. Taxes are $40,000. Depreciation of equipment is $60,000. Amortization of software is $20,000. After these, reported profit is only $130,000.

From a trader’s view, EBITDA stays at $300,000. If next year revenue stays the same but operating costs fall to $650,000, EBITDA rises to $350,000. Even if interest or taxes change, traders may react positively because the core business is improving.

Practical Applications of EBITDA

Practical Uses of EBITDA (Overview)

| Use Case |

What EBITDA Shows |

| Profitability analysis |

Core earnings from normal business operations |

| Interest coverage |

Ability to pay interest from operating earnings |

| EV/EBITDA valuation |

Business value relative to operating earnings |

| Debt-to-EBITDA |

Leverage level and overall debt risk |

1. Evaluating Operating Profitability

EBITDA helps show how efficiently a company earns money from its main business. It is especially useful when comparing similar companies, as it removes differences caused by debt levels or depreciation methods.

2. Debt and Credit Analysis

Lenders and investors use EBITDA to judge whether a company generates enough earnings to meet its debt obligations. Ratios like interest coverage and Debt-to-EBITDA help highlight financial stress early.

3. Mergers and Acquisitions

In acquisitions, especially involving private companies, full cash flow data may not be available. EBITDA offers a consistent way to compare earnings across businesses without being affected by financing structure.

4. Valuation Using EV/EBITDA

The EV/EBITDA multiple compares a company’s total value to its operating earnings. It is widely used in industries where high capital spending makes net profit less reliable.

Pros And Cons Of EBITDA

| Pros of EBITDA |

Cons of EBITDA |

| Focuses on core operating performance by excluding financing and tax effects |

Does not represent actual cash flow |

| Enables easier comparison across companies with different capital structures |

Ignores capital expenditures and reinvestment needs |

| Useful for valuation methods such as EV/EBITDA |

Can overstate profitability for asset-heavy businesses |

| Commonly used in credit analysis and debt covenants |

Vulnerable to manipulation through “adjusted EBITDA” add-backs |

| Helpful in mergers and acquisitions, especially for private companies |

Does not capture working capital movements |

| Removes non-cash accounting effects from depreciation and amortization |

Can mask financial risk when leverage is high |

What EBITDA Represents in Practice

EBITDA is best viewed as a proxy for operating cash flow, not a replacement for it. While it excludes several non-cash items, it does not account for working capital changes or capital expenditures.

Despite this limitation, EBITDA remains a useful indicator of a company’s ability to generate earnings from its operations. When used alongside cash flow and balance sheet analysis, it provides meaningful insight into business quality and sustainability.

How Retail Investors Should Use EBITDA

For retail investors, EBITDA is most useful as a screening and comparison tool, not as a standalone decision metric. Used correctly, it helps narrow down opportunities and identify potential risks before deeper analysis.

1. Start with EBITDA, don’t stop there

Use EBITDA to spot companies with solid core earnings, but always treat it as a starting point rather than a complete assessment.

2. Compare similar businesses only

EBITDA is most useful when comparing companies in the same industry. Differences in capital needs and cost structures make cross-industry comparisons unreliable.

3. Check cash flow next

Always review operating and free cash flow alongside EBITDA. A large gap may signal heavy reinvestment needs, working capital pressure, or accounting issues.

4. Look at capital spending

Strong EBITDA doesn’t guarantee safety or value if a company must constantly reinvest to operate. Capital expenditure trends show how much cash the business really needs.

5. Be cautious with “adjusted EBITDA”

Repeated add-backs can inflate earnings and hide real costs. Treat adjusted EBITDA with skepticism, especially when the same expenses are excluded every year.

6. Use EBITDA to assess debt risk

Ratios like Debt-to-EBITDA and interest coverage help determine whether operating earnings are sufficient to support the company’s debt load.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. Is EBITDA the same as cash flow?

No. EBITDA is not the same as cash flow. While it removes non-cash expenses such as depreciation and amortization, it does not account for changes in working capital, capital expenditures, or debt repayments. As a result, EBITDA can differ significantly from actual cash generated by the business, especially for companies that require ongoing reinvestment.

2. Can EBITDA be negative?

Yes. A negative EBITDA indicates that a company’s core operations are not generating enough revenue to cover operating expenses before financing and accounting adjustments. This often reflects weak pricing power, high cost structures, or an early-stage business model that has not yet reached scale.

3. Is higher EBITDA always better?

Not necessarily. While higher EBITDA can suggest stronger operating profitability, it does not automatically mean the business is financially healthy. EBITDA must be assessed alongside debt levels, capital expenditure requirements, and free cash flow to determine whether earnings translate into sustainable value.

4. Why is EBITDA still widely used?

EBITDA remains popular because it allows analysts and investors to compare operating performance across companies with different capital structures, tax environments, and accounting policies. When used correctly, it provides a standardized view of operating earnings that complements, rather than replaces, other financial metrics.

5. Can investors rely on EBITDA alone?

No. EBITDA should never be used in isolation. A complete analysis requires examining cash flow, balance sheet strength, leverage, and return metrics. EBITDA is best treated as one input within a broader financial framework rather than a standalone measure of business quality.

Summary

EBITDA is best understood as a diagnostic tool, not a conclusion. It helps investors evaluate how a business performs before financing decisions, tax considerations, and accounting treatments shape reported earnings. If used appropriately, it is valuable for comparing operating profitability, assessing leverage, and supporting valuation analysis.

However, EBITDA does not measure cash generation, nor does it reflect the capital required to maintain or grow a business. Ignoring these limitations can lead to overstated conclusions about financial strength or valuation.

The most effective analysis treats EBITDA as a starting point, one component of a broader framework that also incorporates cash flow, balance sheet quality, capital expenditure demands, and long-term financial sustainability.

Disclaimer: This material is for general information purposes only and is not intended as (and should not be considered to be) financial, investment, or other advice on which reliance should be placed. No opinion given in the material constitutes a recommendation by EBC or the author that any particular investment, security, transaction, or investment strategy is suitable for any specific person.